Outline

The rapid proliferation of Global Value Chains (GVCs) has changed the nature of global commerce, and with it, the political contours and economic consequences of trade protection in the 21st century. Trade wars have always been costly, but they are particularity expensive in the GVC era.

This article shares insights from recent research in economics, and explains how protectionist policies could backfire.

The nature of global commerce has changed dramatically over the past 40 years, with the meteoric rise of Global Value Chain (GVC) trade.1 Simply put, countries and companies make goods differently today than in the past. In the 21st century, products are “made in the world” as never before, as firms combine raw materials, inputs, labor, and ideas – the many slivers of value added that ultimately make up a final product – each sourced from around the world according to specific cost-benefit tradeoffs for every component part of the value chain. This GVC phenomenon is made possible by innovations in communications and transportation technologies, together with institutional and market reforms that have allowed scores of countries to join an increasingly-integrated global trading system. GVC trade – measured as a dramatic rise in the trade in value-added subcomponents relative to trade in final goods – is the quantifiable manifestation of this “made in the world” global production revolution.

In turn, the rise of GVC trade has reshaped the economic consequences and political contours of trade protection. Trade wars have always been disruptive, but they are particularly expensive and divisive in the GVC Era.

This article builds on insights from recent research to identify three critical dimensions of GVC trade that promise to make today’s trade wars more economically costly and more politically complex than previous trade wars. Along the way, the discussion highlights distinctive aspects of the recent 2018 trade actions that could carry additional, unintentional costs for the US economy.

The first point is obvious but important: GVCs amplify the effects of tariffs. Because tariffs are (typically) applied to the gross value of a good when it crosses the border, rather than just the “new” value added, every border crossing increases the total tariff-bill associated with production.

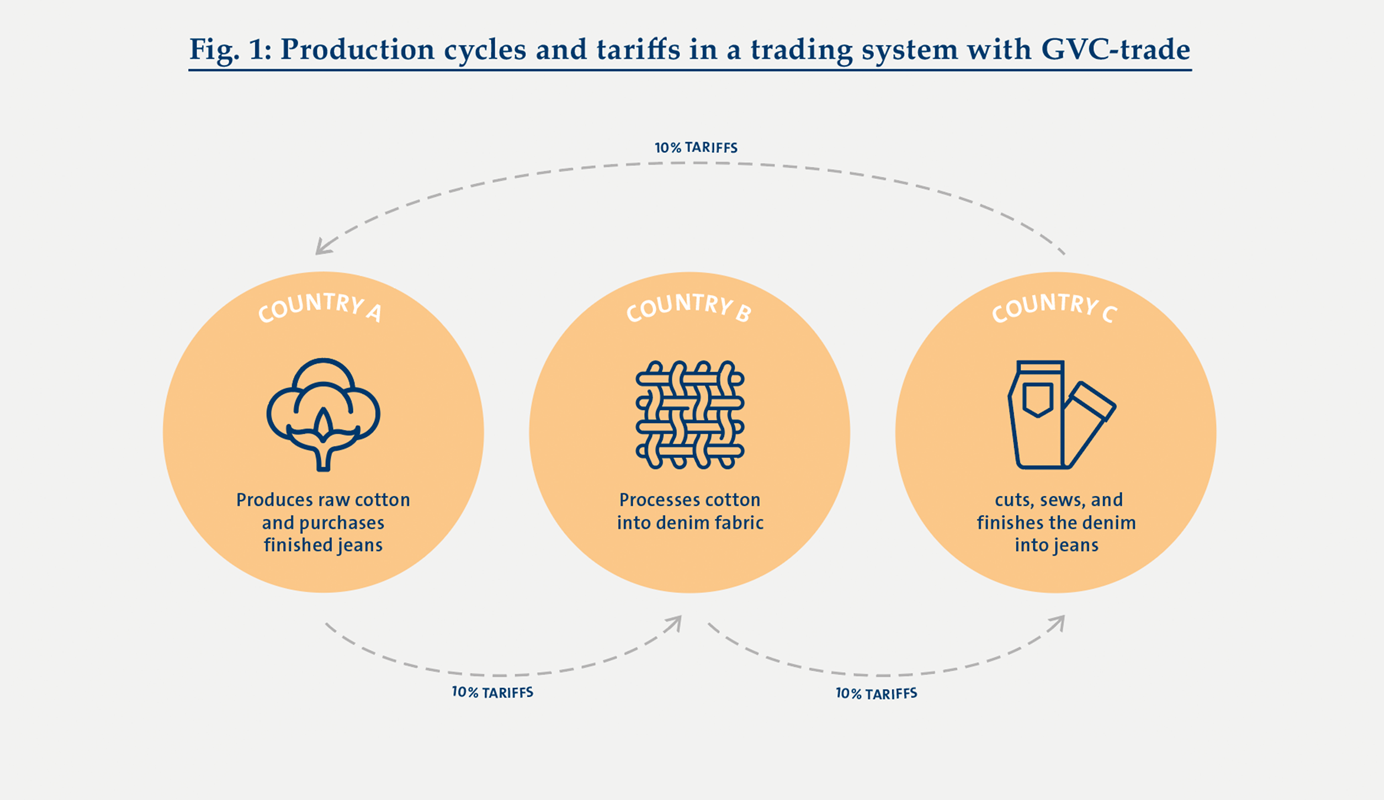

Consider the example in Figure 1. Suppose that a pair of blue jeans is made in three stages: first, raw cotton is grown in country A and exported to country B; then country B processes the cotton into denim fabric, which is exported to country C; finally, country C cuts, sews, and finishes the jeans to be sold, ultimately, in country A. If each country imposes a uniform 10% tariff on all imports, a tariff will be paid three times during the production process, with escalating costs as the gross value of trade increases from raw cotton, to the cotton fabric, to the finished product. Had the jeans been produced start to finish in country C, the tariff would be paid just once (when the final product is shipped to the consumer in country A), and the total cost of production, inclusive of tariffs, would be lower.

The implication is immediate: the costs of higher tariffs in trade war will be greater (potentially many times over) in a trading system with GVC-trade than in an otherwise equivalent world without it. The corollary (discussed further below) is that higher tariffs in general, and trade wars in particular, may induce firms to shorten or otherwise reshape their global supply chains.2

The costs of higher tariffs in trade war will be greater in a trading system with GVC trade

The second distinction concerns not the total cost of a trade war, but the distribution of that cost across different stakeholders. Fundamentally, GVC linkages mean that the burden of tariffs falls differently among consumers, workers, and firms involved throughout the value chain. As explained below, some of the costs of trade protection may ultimately be borne by upstream producers in the country imposing the tariff,3 while some of the producer-side benefits from trade protection enjoyed by local import-competing firms may be passed along to foreign interests.

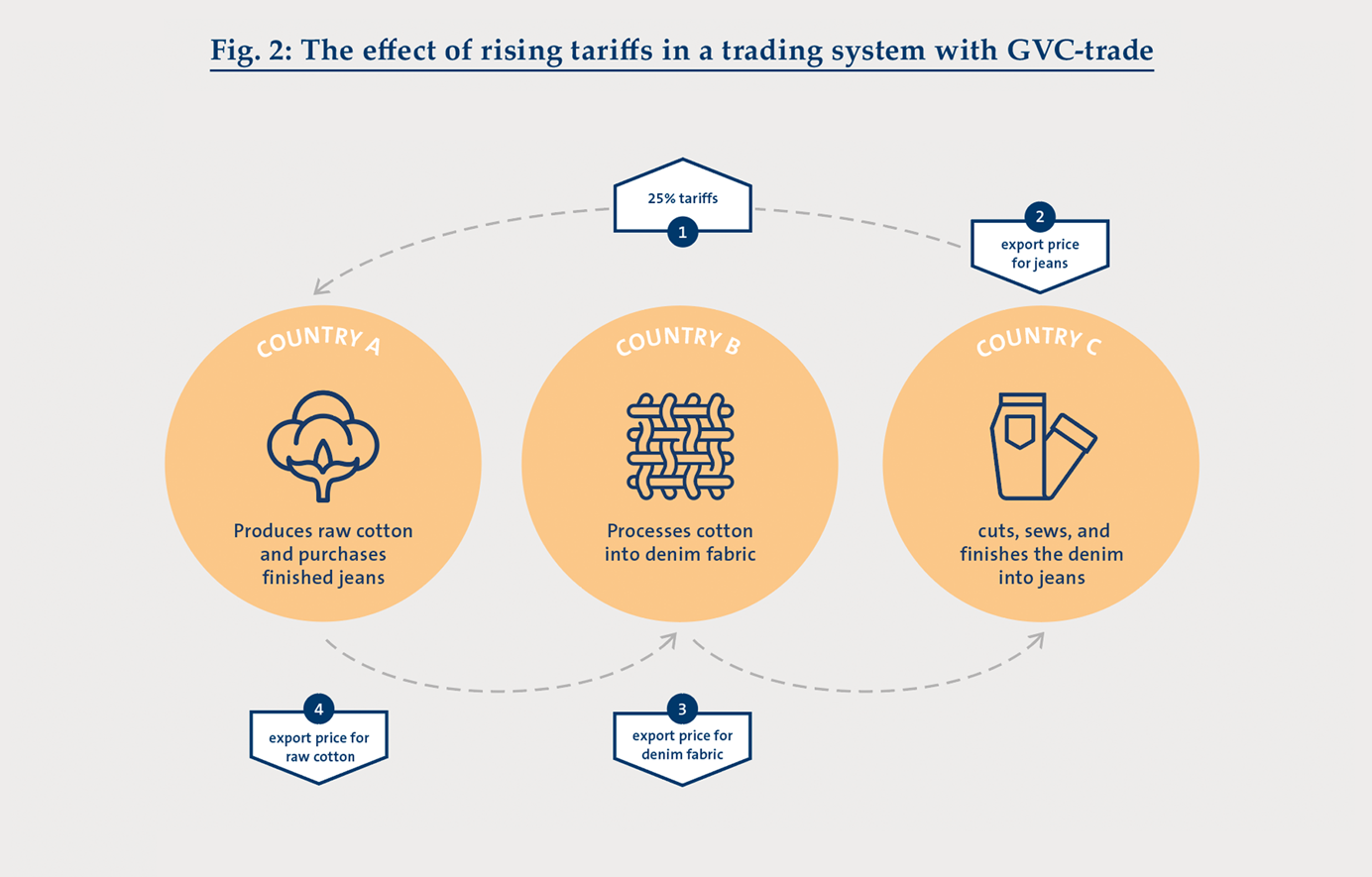

The same example of blue jean production serves to illustrate (Figure 2). Suppose now that country A increases its tariff on all products (including blue jeans) to 25%. If country A’s consumers constitute a sufficient share of global demand for blue jeans, then an increase in country A’s tariff will push down the export price received by the makers of jeans in country C. That is, the incidence of the tariff will be shared by consumers in country A, who pay higher prices, and producers in country C, who receive lower prices, with the government of country A collecting the difference as tariff revenue. By the same logic, if country C’s jeans-producers are an important source of global demand for denim fabric, producers of jeans in country C will be able to pass-on some of the fall in their revenue to producers of fabric in country B, who would then receive a lower export price. In turn, if country B is a sufficiently important market for country A’s raw cotton, the price of cotton in country A will also fall. Thus, ultimately, the costs of country A’s tariffs on imported blue jeans will be shared between country A’s consumers and all of the producers of value added embedded in the imported blue jeans, including, in this example, the producers of raw cotton in country A.

The effects of higher tariffs may extend well beyond the immediate “intentional” targets at the expense of the very country that imposed the new protection

Meanwhile, if country A had a producer of blue jeans competing head-to-head with imports from country C, that producer would gain from the additional protection afforded by the 25% tariff. But if that local producer was owned by a foreign interest, or sourced its inputs from abroad, part of the benefit of that trade protection would again be passed up the value chain, outside of country A. GVC linkages mean that country A’s benefit from tariff protection may be eroded, even as it must internalize more of the costs of its tariff hike.4

The extent to which producers in each country bear the costs of the tariff depend on a host of factors, including market power, bargaining relationships, input customization, trade volumes and more. Whatever the details, the broad implication is the same: GVC trade means that the costs and benefits of higher tariffs – and by extension, trade wars – may extend well beyond the immediate “intentional” targets to include countries and companies around the world, even at the expense of the very country that imposed the new protection at the outset.

The third point recognizes that GVCs are themselves determined by market forces. Because GVC structure is the result of strategic sourcing and foreign investment decisions of globally-engaged firms, tariffs may have large, long-lasting, and unanticipated consequences for the pattern of global production. If rising tariffs (or even just the threat of a trade war) causes firms to change how and where products are made in the world, this additional production dislocation will carry additional efficiency, job, profit, and welfare losses. Moreover, given the complex calculus faced by firms responding to changes in the global economic landscape, there is good reason to believe that global firms may not respond the way the importing country wants or expects.

Production dislocation is particularly likely under a tit-for-tat tariff escalation, in which multiple countries raise tariffs at the same time. All else equal, higher tariffs give firms an incentive to consolidate their global supply networks into fewer countries, border crossings, and (thus) vulnerabilities. But where firms choose to consolidate that production depends on a host of factors, including proximity not only to expected consumers, but also raw material, critical input suppliers, local economic regulations, policy certainty, access to skilled and low-cost labor, and more.

To the extent that some of the new US-imposed tariffs in 2018 were designed to induce producers to “reshore” production in the US, they may have the unintended consequence of causing firms to balkanize their production networks somewhere else. “America first” could backfire.

“America first”

could backfire

A noteworthy irony, given President Trump’s stated goal to bring jobs back to US shores, is that the administration has imposed new tariffs disproportionately on imported intermediate goods5— the very inputs that are necessary for US manufacturers to produce and sell their products competitively in the US and global markets. If the intent is to induce US manufactures to “re-shore” production to the US (or to dissuade US firms from moving final assembly/downstream production overseas), lower tariffs on imported intermediate goods would be in order. Higher tariffs on intermediate goods – together with increased uncertainty over the future of US tariff policy more generally6 – seem all but designed to induce firms to shift their current production patterns away from the US and into “factory Asia” or “factory Europe”.

Global firms seem to appreciate the importance of these GVC linkages and what they mean for the potential escalating and unanticipated costs of trade wars. The US Chamber of Commerce has been a relentless advocate for a quick and amicable resolution of the 2018 trade frictions. At the same time, the United Steelworkers union, which represents nearly 1 million US worker-members in manufacturing, metals, forestry and beyond – industries that employ workers up and down the value chain across myriad traded products – was an outspoken critic of both renegotiating NAFTA and the US steel and aluminum tariffs against Canada. Perhaps most notably, until recently, many governments had been implementing policies consistent with a sophisticated understanding of the relationship between GVCs and trade policy. According to several studies, the contours of GVC linkages and firms’ global sourcing operations were reflected in trade policy before the 2018 trade war, not least in the US.7

How will firms shift, consolidate, and potentially balkanize their production to mitigate the costs of tit-for-tat tariffs and the uncertainty of future trade wars?

Early evidence suggests that even in the very short run, the 2018 trade war is taking a toll on US firms and consumers.8 The key question in the months and years to come, is how, if these tariffs continue, they begin to feed back through global value chains at the expense of firms and workers in the US, China, and around the world. How, ultimately, will firms shift, consolidate, and potentially balkanize their production to mitigate the costs of tit-for-tat tariffs and the uncertainty of future trade wars? The consequences of this trade war may be slow to unfold, and long lasting once they do.

- See Baldwin (2016) for an overview of the GCV phenomenon and Johnson and Noguera (2017) for an authoritative empirical examination.

- See Johnson and Moxnes (2016); Head and Mayer (2016); and Antras and De Gortari (2017) for efforts to quantify the extent of potential global supply chain dislocation in response to rising trade costs.

- See Blanchard (2010) and (2015) for formal treatment and broader policy implications of this point.

- See Blanchard, Bown, and Johnson (2016).

- Bown and Zhang (2019).

- Handley and Limao (2017) find that the economic costs of trade policy uncertainty can be as large as tariffs themselves.

- Blanchard, Bown and Johnson (2016) and Blanchard and Matschke (2015) provide empirical evidence that GVC linkages and the pattern of multinational firms’ global sourcing activities (respectively) influence tariff setting in practice.

- Amiti, Redding and Weinstein (2019) and Fajgelbaum, Goldberg, Kennedy, and Khandelwal (2019) find evidence that in the past year, most of the costs of

the new 2018 US tariffs have been passed through to US consumers as higher prices. The first paper finds additionally that the 2018 tariff increases have already induced significant changes in US firms’ supply networks and a decline in firms’ and consumers’ access to imported varieties.

- Antras. P. and A. De Gortari (2017) “On the Geography of Global Value Chains” NBER Working Paper 395246.

- Amiti, M., S. Redding, and D. Weinstein (2019) “The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on US Price and Welfare,” CEPR Discussion Paper 13564, March 2019.

- Baldwin, R. (2016) The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Blanchard, E. (2010) “Reevaluating the Role of Trade Agreements: Does Investment Globalization make the WTO Obsolete?” Journal of International Economics 82(1): 63-72

- Blanchard, E. (2015) “A Shifting Mandate: International Ownership, Global Fragmentation, and a Case for Deeper Integration under the WTO” World Trade Review 14(1): 87-99

- Blanchard E. and X. Matschke (2015) “U.S. Multinationals and Preferential Market Access,” Review of Economics and Statistics 97(4): 839-854

- Blanchard, E., C.P. Bown and R. Johnson (2016) “Global Supply Chains and Trade Policy,” NBER Working Paper 21883, January 2016.

- Bown C. and E. Zhang “Measuring Trump’s 2018 Trade War: 5 Takeaway” Peterson Institute for International Economics, February 15, 2019

- Fajgelbaum, P., P. Goldberg, P. Kennedy, and A. Khandelwal

“The Return to Protectionis,” NBER Working Paper 25638, March 2019 - Handley, K. and N. Limao (2017) “Policy Uncertainty, Trade and Welfare: Theory and Evidence for China and the U.S.” American Economic Review 107 (9): 2731-83.

- Head, K. and T. Mayer (2016) “Brands In Motion: How Frictions Shape Multinational Production,” CEPR Discussion Paper 10797. Summary and extensions available from VoxEU.org as “Reversals of Regional Trade Agreements: Consequences of Brexit and Trumpit for the Multinational Car Industry” November 12, 2016

- Johnson, R. and A. Moxnes (2016) “Technology, Trade Costs, and the Pattern of Trade with Multistage Production,” Working Paper ( https://sites.google.com/

site/robjohnson41/ ).research/multistage - Johnson, R. and G. Noguera (2017) “A Portrait of Trade in Value Added over Four Decades,” Review of Economics and Statistics 99(5), 896-911.

More Issues

Variable Carbon Pricing and the Environmental Gains from Trade

Optimal Carbon Tax for Maritime Shipping?

The Global Diffusion of Clean Technology

The Sustainable Globalization Index

The Distributional Effects of Carbon Pricing:

The Green Comparative Advantage:

Global Trade

The EU Emissions Trading System

The Hidden Green Sourcing Potential in European Trade

The European Green Deal

Post-COVID19 resilience

Africa’s Trade Potential

Buy Green not Local

A New Hope for the WTO?

Crumbling Economy, Booming Trade

Pandemic and Trade

The Dynamics of Global Trade in Times of Corona