Outline

There has been a sharp increase in regional trade agreements (RTAs) in recent decades, most of which take the form of free trade agreements (FTAs). Not only have RTAs risen in number but they have also become “deeper” over time, encompassing provisions that go beyond tariff reductions and traditional trade policies. These “new generations” FTAs pose a challenge for EU trade policy, since the EU’s ability of covering trade and investment policies in one single comprehensive economic agreement has been crippled in the aftermath of the chaos surrounding the CETA agreement. In addition, Europe is experiencing an increasing opposition towards globalization, with protests all around the continent against “deep” trade agreements, and the influence of powerful multinational corporations in determining their content. In view of these new challenges of globalization, this article analyzes the European Union’s ability to ratify deep and comprehensive free trade agreements.

Recent decades have seen a proliferation of regional trade agreements (RTAs). There are currently more than 300 RTAs in force, with many more being negotiated, most of which take the form of free trade agreements (FTAs). RTAs have not only risen in number but have also become “deeper” over time, encompassing provisions that go beyond tariff reductions and traditional trade policies, such as rules on investment and intellectual property rights (IPR) or Investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism. A prominent argument is that these rules are needed to promote and facilitate the operation of global supply chains. As pointed out by Baldwin (2011), when firms set up production facilities abroad – or form longterm ties with foreign suppliers – they can gain from trade agreements not only through the elimination of tariffs, but also through the inclusion of provisions that help to protect their tangible and intangible assets in foreign markets. This argument is formalized by Antràs and Staiger (2012), who develop a theoretical model showing that in the presence of offshoring of intermediate inputs, deep integration is necessary to achieve internationally efficientpolicies.

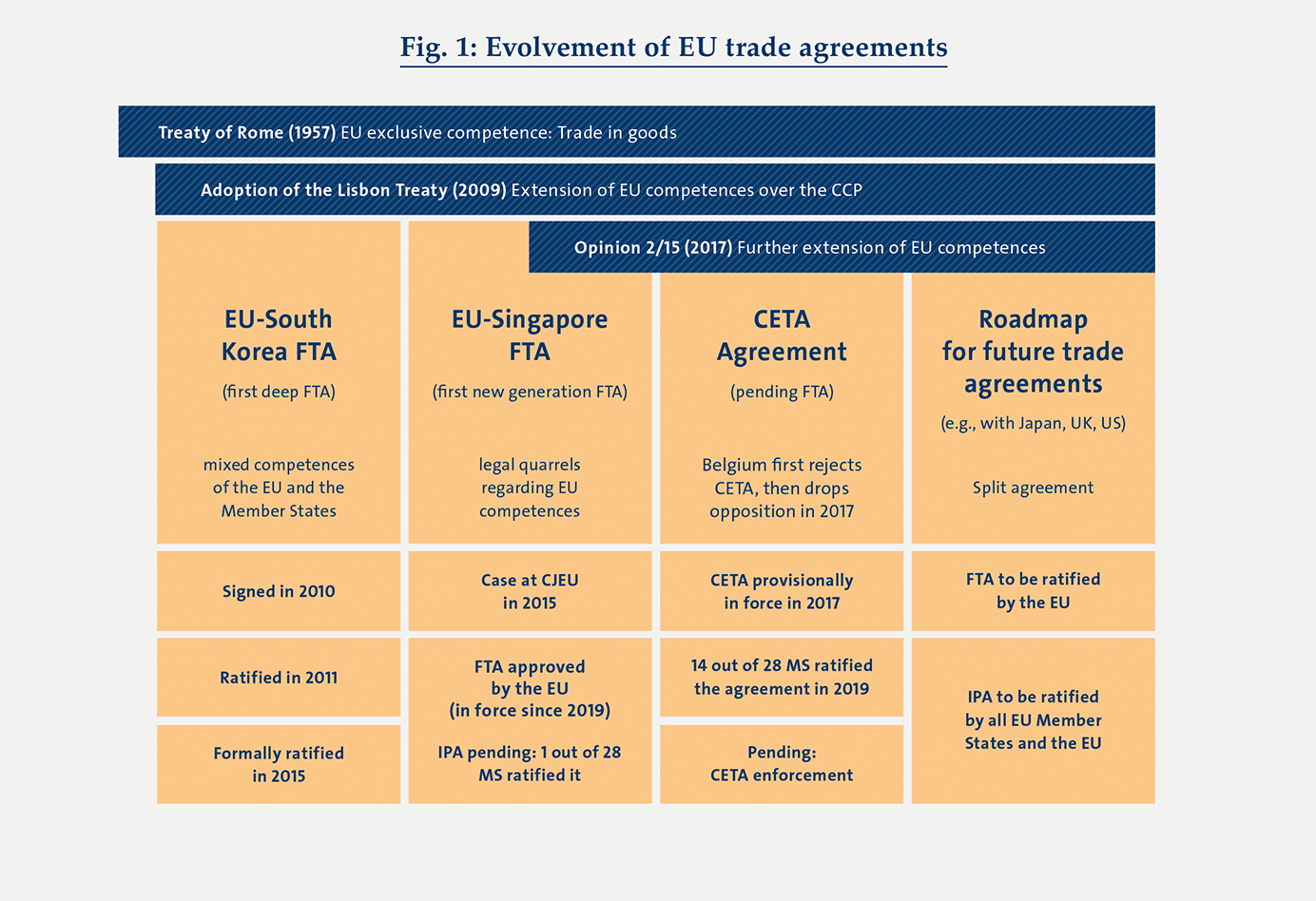

In view of these new challenges of globalization, it is interesting to analyze the European Union’s ability to ratify deep and comprehensive free trade agreements. Trade in goods has always been an exclusive competence of the European Union (since the Treaty of Rome of 1957), while issues related to services, intellectual property rights (TRIPs) or Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) fell under the mixed competences of the EU and the member states. As a consequence, deep FTAs that encompassed provisions on investments, government procurement, or IPR had to be ratified by the Commission, the European Parliament (EP), as well as European Members States following their legislative procedure. The EU-South Korea FTA was the first of these deep FTAs. The agreement was signed on October 2010 and ratified by the EP in February 2011. Due to its mixity, it was provisionally applied since July 2011 (only for the issues that were of exclusive competence of the EU) and it was formally ratified in December 2015, when the approval procedures in all 28 member states were concluded. The ratification mechanism gave almost unlimited veto power to EU sovereign governments. Italy, for example, had deep concerns about the potential repercussions of the FTA to its automotive sector, and was the last country to conclude its ratification procedure, delaying the final and full adoption of the FTA by more than 3 years.

In order to address this issue, the European Union sought to increase its competences in the area of external trade policy, formally known as Common Commercial Policy (CCP). The adoption of the Lisbon Treaty (December 1, 2009), clarified and extended the EU competences over the CCP1. As a result, all key aspects of external trade – in goods and services, FDI, and commercial aspects of intellectual property – were under the exclusive competence of the EU2. The objective of this centralization of competences was to simplify the procedure for the adoption of deep farreaching FTAs. Moreover, the EU became the only relevant negotiator in the field of international investments, increasing its bargaining power when making trade and investment deals with its partners.

After the 2009 adoption of the Lisbon Treaty, the EU became the only relevant negotiator in the field of international investments.

Following the adoption of the Lisbon Treaty, the EU started negotiating new and deeper FTAs with its trade partners, the so-called “new generation” trade agreements. These FTAs contain, in addition to the classical provisions on the reduction of customs duties and non-tariff barriers to trade in goods and services, provisions on investments and investment protection, including the establishment of the Investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism. The first agreement of this kind was the EU-Singapore FTA (EUSFTA). It was to become the prototype of all future bilateral trade negotiations, for example with the other ASEAN countries (Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines, Myanmar/Burma), and with Japan. The trade agreement with Singapore opened new controversies between European Member States and the Commission, with the former claiming that the latter overstepped its power. The significant legal quarrels regarding EU competences to exclusively conclude the EUSFTA came at a high reputational cost for the Union, casting doubt on its ability to ratify the agreement. Aiming to reinstate clarity in this matter, in 2015 the Commission sought an opinion from the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU).

The Court was asked which provisions of the EUSFTA - and subsequently of all future “new generation” FTAs - fell within the EU’s exclusive competence, and which remained within shared or exclusive competences of the Member States. On 16 May 2017, the CJEU issued its response in Opinion 2/153. On the one hand, the Court extended EU competences in the Common Commercial Policy far beyond what was stated in Article 207(1) of the TFEU (for the article see footnote 2), ruling that provisions on non-commercial aspects of intellectual property rights, air and maritime transport services as well as fundamental labor and environmental standards also fell within the scope of the EU’s exclusive competence. At the same time, the CJEU stated that the EUSFTA could not be concluded by the EU alone, as the Agreement was not covered by the exclusive competence of the EU in its entirety: provisions on non-direct investments and the ISDS mechanism fell within a competence shared between the European Union and its Member States. As a consequence, the investment chapter of the FTA have to be ratified by all EU national parliaments to enter into force.

The legal quarrels around EUSFTA came at a high reputational cost for the EU, casting doubt on its ability to ratify the agreement.

In July 2016, before the ruling of the Court, the European Commission concluded the negotiations of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with Canada. To allow for a swift signature and provisional application of the agreement at the EU-Canada Summit of October 2016, and still awaiting for the CJEU Opinion, the Commission decided to propose CETA as “mixed” agreement, involving national parliaments in the ratification process. This backlashed when the Wallonian parliament, one of the three regional parliaments of Belgium, rejected the CETA agreement. With a last-minute compromise, Wallonia decided to drop temporarily its opposition to the deal, allowing for its final signature, and on September 2017, the agreement has provisionally entered into force. It will enter into force fully and definitively when all EU Member States parliaments have ratified the agreement, so far only 14 out of 28 MS did it. At the same time, the CETA agreement can be scuppered altogether if only a single MS formally rejects it. Several European countries have threatened to reject and block the deal, among them Poland, the Wallonian federal region of Belgium, and Italy.

As the chaos, and future uncertainty, surrounding the CETA agreement has shown, “mixed” FTAs are not a viable option for the EU. At the same time, Opinion 2/15 lacked in delivering to the EU the full power necessary to ratify deep and comprehensive trade agreements on its own. This opinion has substantial political and economic implications that extend beyond the specific EU-Singapore relationship, and have repercussions on all future EU external trade relations.

On one hand, it strengthens the role of the EU institutions – namely the Commission, the Council and the Parliament – in setting the common commercial policy. It also broaden the scope of these trade negotiations, by including sustainable development (labor protection and environmental issues) among the exclusive competences of the EU. On the other hand, it cripples EU’s ability of covering trade and investment policies in one single comprehensive economic agreement, which would have been crucial to answer to the real challenges of our contemporary globalized world. In concl-usion, the best way to interpret Opinion 2/15 is by reading it as a roadmap to avoid mixity in FTAs.

All ongoing trade negotiations have been adjusted to create two standalone agreements: a Free Trade Agreement and an Investment Protection Agreement (IPA). This split will allow the EU to swiftly approve the FTA, while waiting for its Member States to approve the IPA. This procedure has not been applied only to the ongoing negotiations with Singapore, Japan and Vietnam, but it has been adopted by the European Council as a new approach in negotiating and concluding FTAs4.

Split FTAs are the future of EU trade negotiations.

Being unable to operate with a single voice, the EU is less of a reliable partner for these “new generations” FTAs. Moreover, all of this discussion made trade agreements political again. We are experiencing an increasing opposition towards globalization, with protests all around Europe against “deep” trade agreements such as CETA and the TTIP (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership), and the influence of powerful multinational corporations in determining their content. This resonates with Rodrik (2018)’s argument that deep trade agreements are “the result of rent-seeking, self-interested behavior on the part of politically well-connected firms — international banks, pharmaceutical companies, multinational firms”. The major concerns are often related to the investment protection provisions within these agreements. Giving full veto power to member states over these issues, limits extensively EU’s ability to ratify deep and comprehensive FTAs.

Being unable to operate with a single voice, the EU is less of a reliable partner for “new generations” FTAs.

Finally, the question that remains unanswered is if EU trade partners will be willing to start two separate negotiations for a FTA and an IPA, knowing that the likelihood of the latter being approved might be low, or at least take an extremely long time.

- Article 3(1)(e) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) states that “The Union shall have exclusive competence in the following areas: [...] common commercial policy”

- Article 207(1) of the TFEU states that “The common commercial policy shall be based on uniform principles, particularly with regard to changes in tariff rates, the conclusion of tariff and trade agreements relating to trade in goods and services, and the commercial aspects of intellectual property, foreign direct investment, the achievement of uniformity in measures of liberalisation, export policy and measures to protect trade such as those to be taken in the event of dumping or subsidies. The common commercial policy shall be conducted in the context of the principles and objectives of the Union’s external action”.

- Opinion 2/15 of the Court (Full Court), Opinion pursuant to Article 218(11) TFEU [2017] ECLI:EU: C:2017:376 http://curia.europa.eu/

juris/ document/ document.jsf ?text=&docid=190727&doclang=EN - Council of the EU, 8622/18: “Draft Council conclusions on the negotiation and conclusion of EU trade agreements“ (May 8, 2018) http://data.consilium.europa.eu/

doc/ document/ ST-8622-2018-INIT/ en/pdf

- Antràs, P., and R. W. Staiger (2012). “Offshoring and the Role of Trade Agreements,” American Economic Review 102, 3140-3183.

- Baldwin, R. (2011). “21st Century Regionalism: Filling the Gap Between 21st Century Trade and 20th Century Trade Rules,” CEPR Policy Insight 56.

- Rodrik, D. (2018). “What Do Trade Agreements Really Do?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 23, 73-90.

More Issues

Variable Carbon Pricing and the Environmental Gains from Trade

Optimal Carbon Tax for Maritime Shipping?

The Global Diffusion of Clean Technology

The Sustainable Globalization Index

The Distributional Effects of Carbon Pricing:

The Green Comparative Advantage:

Global Trade

The EU Emissions Trading System

The Hidden Green Sourcing Potential in European Trade

The European Green Deal

Post-COVID19 resilience

Africa’s Trade Potential

Buy Green not Local

A New Hope for the WTO?

Crumbling Economy, Booming Trade

Pandemic and Trade

The Dynamics of Global Trade in Times of Corona