Impact Series: 01–21

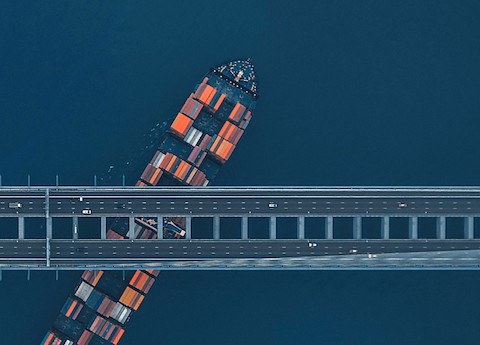

Crumbling Economy, Booming Trade

The Surprising Resilience of World Trade in 2020

Outline

How can it be that we experience a historic recession, but international trade is doing just fine? In this Kühne Impact Series, we argue that the COVID-19 recession is one in which non-tradable services suffer but tradable goods thrive. Reasons include that (i) consumption of in-person services is restricted; (ii) demand for consumer durables is strong; (iii) demand for medical goods is high; and (iv) online shopping is popular.

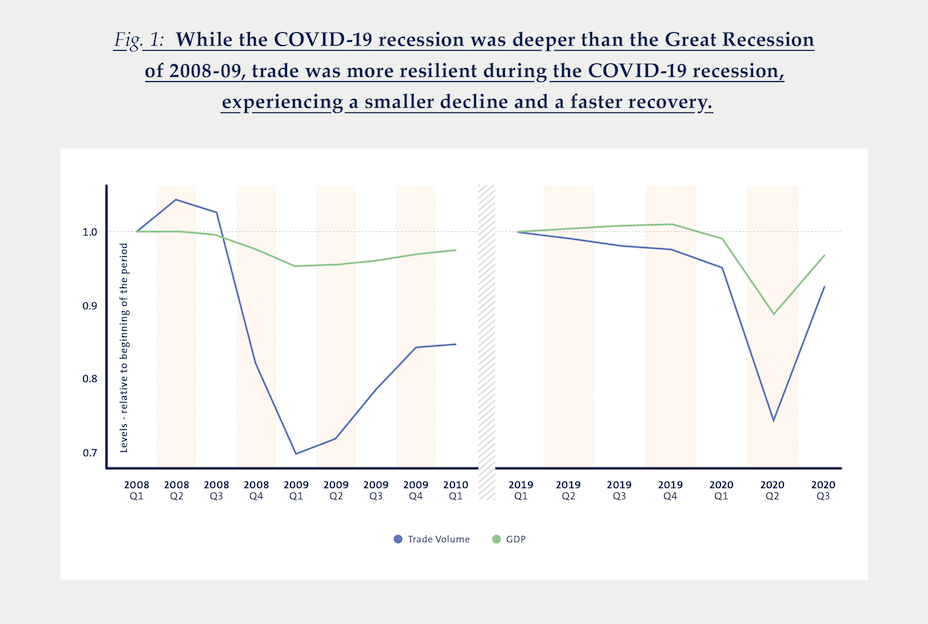

The COVID-19 recession is the deepest recession since the end of the Second World War. For example, the GDP of OECD countries contracted by a staggering -12.2 % during the COVID-19 recession between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020 (the two quarters preceding the trough). As a point of comparison, the GDP of OECD countries con- tracted by a much smaller -4.6% during the Great Recession of 2008-09 between the second quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009 (the three quarters preceding the trough).

Yet, international trade has been surprisingly resilient in 2020. The export volumes of OECD countries fell by 24% during the first two quarters of 2020 but were already back to 95% of their pre-crisis level at the end of the third quarter of 2020. During the Great Recession, in contrast, the export volumes of OECD countries fell by 32% over the same time span (two quarters - 2008-Q4 and 2009-Q1) and took more than two years to recover (in 2010-Q1, so almost a year after the trough of the recession, export volumes were still only at 85% of their pre-crisis level).

The COVID-19 recession is the deepest recession since the end of the Second World War. Yet, international trade has been surprisingly resilient in 2020.

In this Kühne Impact Series, we propose an explanation for the surprising resilience of world trade in 2020 and the associated decoupling of global trade and GDP dynamics. We base our explanation on an intuitive conceptual framework in which trade flows de-pend on the (i) supply of tradable goods by firms, (ii) the demand for tradable goods by firms and house-holds, and (iii) trade costs (custom duties and taxes, but also transportation costs and export credits).

The dramatic drop in world trade at the onset of the pandemic was the result of a “perfect storm”.

From perfect storm to isolated crisis

The dramatic drop in world trade at the onset of the pandemic was the result of a “perfect storm”. In particular, the supply of traded goods was interrupted by lockdowns and plants closures; the demand for traded goods plummeted due to increased income uncertainty, raising unemployment and social distancing; and trade costs skyrocketed due to export restrictions, grounded planes, and closed borders. Hence, the pandemic had an adverse effect on all major determinants of global trade, which explains its initial collapse. The subsequent recovery of global trade is due to several factors:

First, global supply recovered quickly. The key driver of this was the spectacular rebound of the Chinese economy. Despite a large drop in GDP in the first quarter of 2020, China only experienced a very short V-shaped recession. Chinese GDP was almost back to its pre-pandemic level by the end of March 2020. Importantly, China’s manufacturing plants were open and running during the most severe part of the lockdowns in Western economies (when plants were closed in Europe or the United States), and therefore maintained a level of production that could compensate the initial collapse of the supply of goods worldwide.

Later, Europe and the United States also learned to cope better with the pandemic but never quite man- aged to replicate China’s success.

Second, trade costs fell again quickly. Export restrictions were lifted as early as April 2020, thereby reducing the initial difficulties associated with closed borders. On top of this, fuel prices hit a record low in 2020, reducing transportation costs. The price of crude oil per barrel was around US$55 in 2019, where- as it was less than US$20 in the first quarter of 2020.

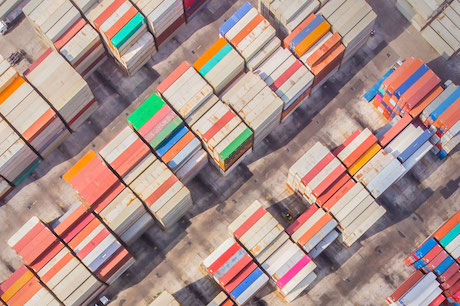

Third, global demand for tradable goods quickly recovered. We now take a closer look at this part of the story because it also plays a central role in our broader argument.

A recession in services

Our key point is that the demand for tradable goods quickly rebounded while the demand for non-tradable services remained low. This explains the decoupling of global trade and GDP dynamics and therefore also the surprising resilience of global trade. Trade and GDP dynamics can decouple because GDP has many non-tradable components. For example, non-tradable goods and services represent 65% of U.S. GDP.

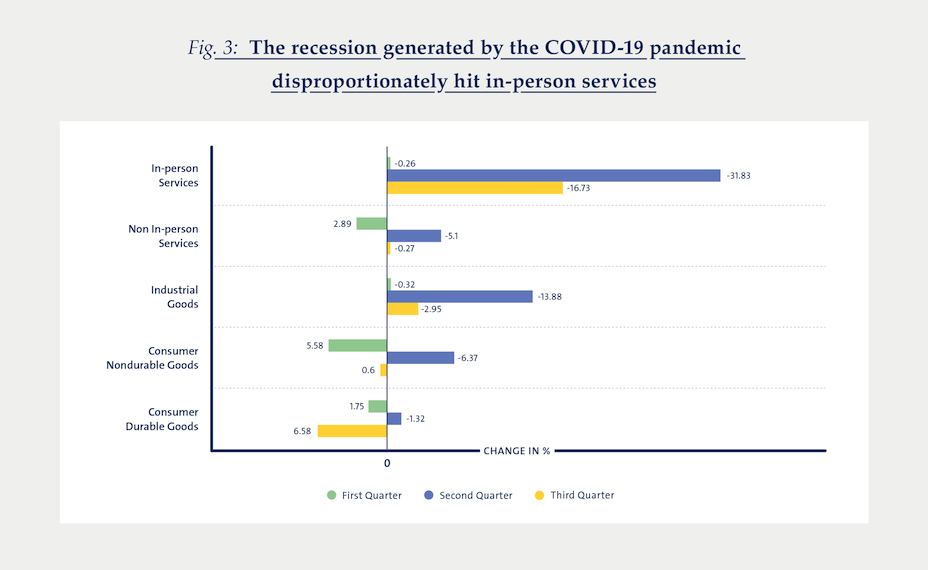

In particular, U.S. national accounts data reveals that services requiring physical in-person interactions were both the key driver of the downturn in the second quarter of 2020 as well as the main reason why GDP remained low in the third quarter of 2020. Consumer durables, on the other hand, only took a small hit in the second quarter of 2020 and even boomed in the third quarter of 2020 relative to the previous year. This points to a shift in consumer expenditure away from predominantly non-traded in-person services (such as restaurants, haircutting salons or cleaning services) towards predominantly traded consumer durables (such as computers, furniture, and other home appliances).

This interpretation is also consistent with recent research by Raj Chetty (Harvard University) and co- authors who show that consumers overwhelmingly spent the money they received through fiscal stimuli on durable goods.1

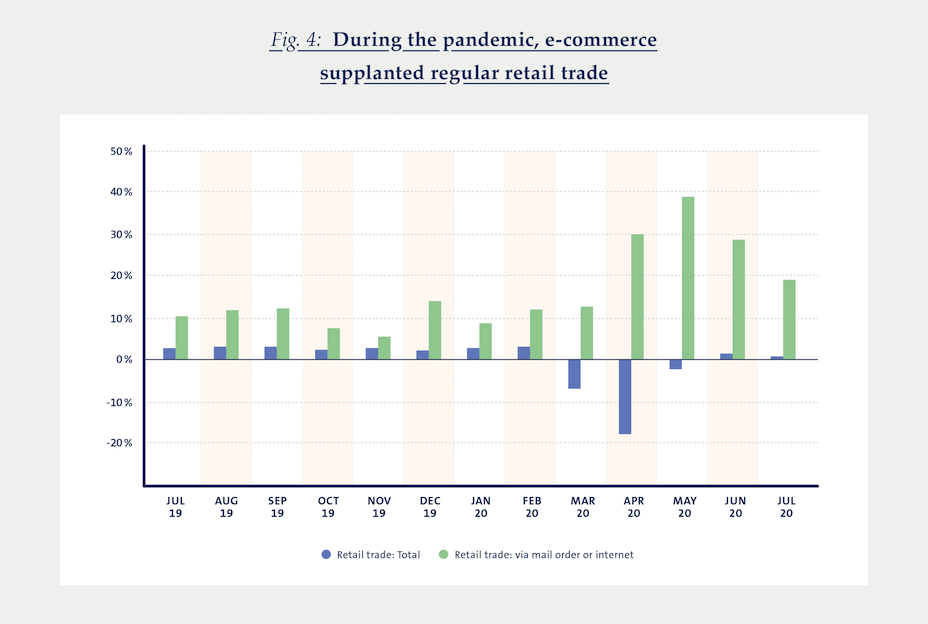

There are a number of plausible explanations for this substitution in consumer spending away from non- traded services towards traded goods. First, the prevailing sanitary measures severely restricted the possibility to consume in-person services. Second, the need to work from home has pushed consumers to invest in electronics and other consumer durables. Third, the pandemic has created its own demand for traded goods such as pharmaceuticals, medical apparel (goggles, gloves), and obviously masks. For example, trade volumes of FFP2 and FFP3 masks – which are mainly produced in China – increased 15-fold between February and May 2020. And fourth, there has been a surge in online shopping (with an average increase in turnover of 16% relative to 2019), which likely also added to the demand of tradable goods.

Our key point is that the demand for tradable goods quickly rebounded while the demand for non-tradable services remained low.

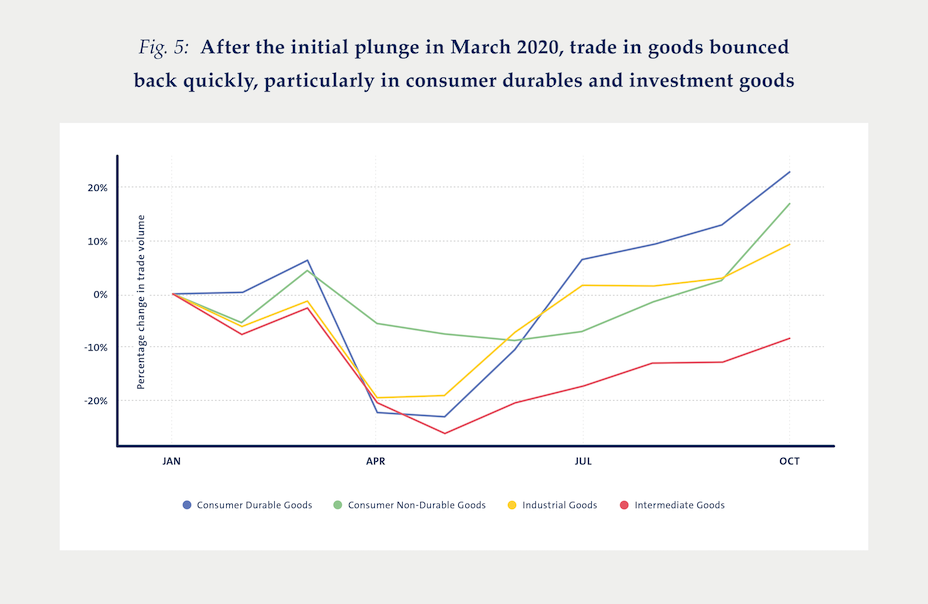

This shift in spending towards tradable goods is also the key difference between the COVID-19 recession and the Great Recession of 2008–2009. In particular, Jonathan Eaton (PennState) and co-authors showed that the collapse in demand in 2008–2009 shifted final spending away from tradable goods, particularly by reducing investment in durable goods by firms.2 They estimate this shift to account for almost two- thirds of the collapse in global trade relative to GDP during that time. In today’s pandemic, trade in investment goods and consumer durables were instead on the rise as early as May 2020.

Conclusion – A recession that favors demand for trade

So, how can it be that we experience a historic recession, but international trade is doing just fine? The reason is that, following an initial collapse, the COVID-19 recession developed into one where non-tradable services suffer and tradable goods thrive. Plausible explanations for this are that (i) the lockdown measures have made it all but impossible to consume in-person services; (ii) the need to work from home has increased spending on consumer durables; (iii) the pandemic has directly created demand for tradable medical goods; and (iv) a surge in online shopping has favored tradable goods.

An open question is whether this demand for trade is sustainable. Large parts of the economy are currently on “life support”, with government programs and business owners covering huge losses to keep business afloat. Without a comprehensive recovery, these parts of the economy will eventually collapse with uncertain implications for global trade.

- Chetty, R. and Friedman, J. N., and Hendren, N. and Stepner, M. November 2021

The Economic Impacts of COVID-19: Evidence from a New Public Database Built Using Private Sector Data - Eaton, J. and Kortum, S. and Neiman, B. and Romalis, J. 2016

Trade and the Global Recession

More Issues

Variable Carbon Pricing and the Environmental Gains from Trade

Optimal Carbon Tax for Maritime Shipping?

The Global Diffusion of Clean Technology

The Sustainable Globalization Index

The Distributional Effects of Carbon Pricing:

The Green Comparative Advantage:

Global Trade

The EU Emissions Trading System

The Hidden Green Sourcing Potential in European Trade

The European Green Deal

Post-COVID19 resilience

Africa’s Trade Potential

Buy Green not Local

A New Hope for the WTO?

Pandemic and Trade

The Dynamics of Global Trade in Times of Corona

EU Trade Agreements

Past, present, and future developments