Impact Series: 02–21

A New Hope for the WTO?

Past achievements, current

challenges, and planned reforms

Outline

The World Trade Organization (WTO) has a new Director General, and we take her appointment as an opportunity to brief the reader on this important international organization. In particular, we (i) explain its past achievements, (ii) discuss its current challenges, and (iii) summarize its planned reforms.

Policymakers now have a historic opportunity to reform the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO has a new Director General, the US has a new President, and the recent experience of the China-US trade war and the COVID-19 crisis have illustrated the urgent need for reform. In this Kühne Impact Series, we brief the reader on this important public policy issue by explaining the WTO’s past achievements, its current challenges, and its planned reforms.

The WTO and its successes over the past 25 years

The WTO is the most important institution of the world trading system. It is an international organization governing the trade relationships between 164 member countries, which jointly account for 96% of global trade and 97% of global GDP. The WTO is built around three main agreements, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) regulating goods trade, the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) regulating services trade, and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) regulating intellectual property rights.

The WTO was established in 1995 in response to the growing complexity of the global economy. It built on the GATT, which had been governing world trade since 1947. While the objective of the GATT was essentially limited to reducing tariffs and related trade barriers, the WTO has a much broader mandate, encompassing issues like services trade, intellectual property rights, dispute settlement, subsidies, regulation, and investment. In trade economist lingo, the WTO therefore pursues a “deep integration” agenda, in contrast to the GATT’s earlier “shallow integration” approach.

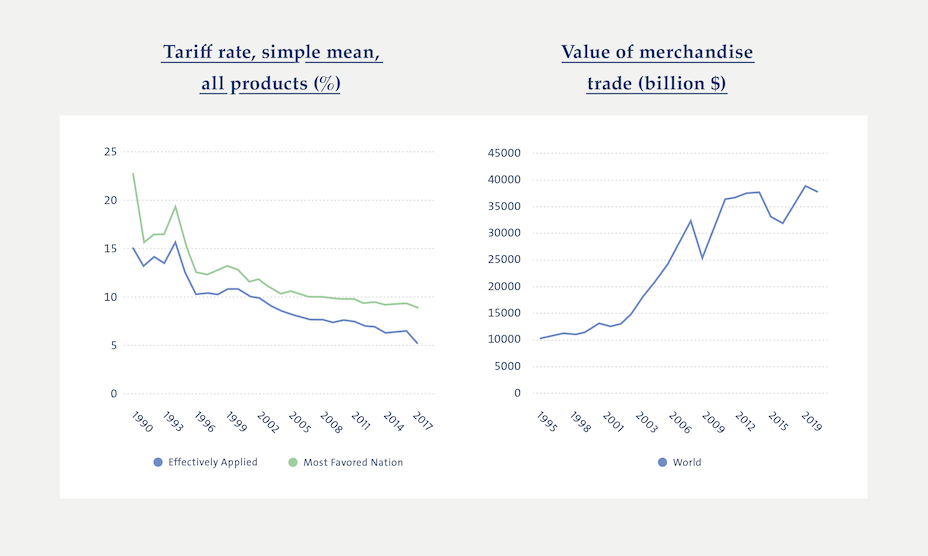

Despite its much more ambitious agenda, the WTO’s success was so far largely limited to further advancing the shallow integration process initiated under the GATT. Under its auspices, average tariffs more than halved (from 12% in 1995 to 5% in 2017) and world trade nearly quadrupled in dollar value terms.1 Moreover, trade policy cooperation remained strong even during severe crises like the Great Recession of 2008-09, at least until the outbreak of the China-US trade war. The most important milestone in this regard was clearly China’s accession to the WTO in 2001.

The WTO’s major challenges

While the WTO deserves credit for these achievements, they still fall far short of its initial goals. One challenge is that WTO members are bitterly divided over essentially all deep integration issues so that it has proven impossible to make any progress on that front. An example of this divide is the never-ending conflict between rich and poor countries about stronger intellectual property rights protection, which rich countries support and poor countries oppose. Another challenge is that the WTO has been unable to keep up with some important new trade policy issues such as e-commerce or data governance.

There are two closely related symptoms of this impasse: First, the WTO has been unable to make any significant progress through multilateral trade negotiations, a hallmark of the world trading system under the GATT. What stands out is the failure of the Doha Development Round, which started in 2001 and ended 7 years later without reaching any agreement, and with reciprocal accusations from the largest economies in the world (US, EU, India and China) for its failure. In 2013, the WTO reached the first, and only, multilateral agreement approved by all its members since its creation – the Bali Package – approving only a very small portion of the Doha Development Agenda.

The WTO has been unable to make any significant progress through multilateral trade negotiations.

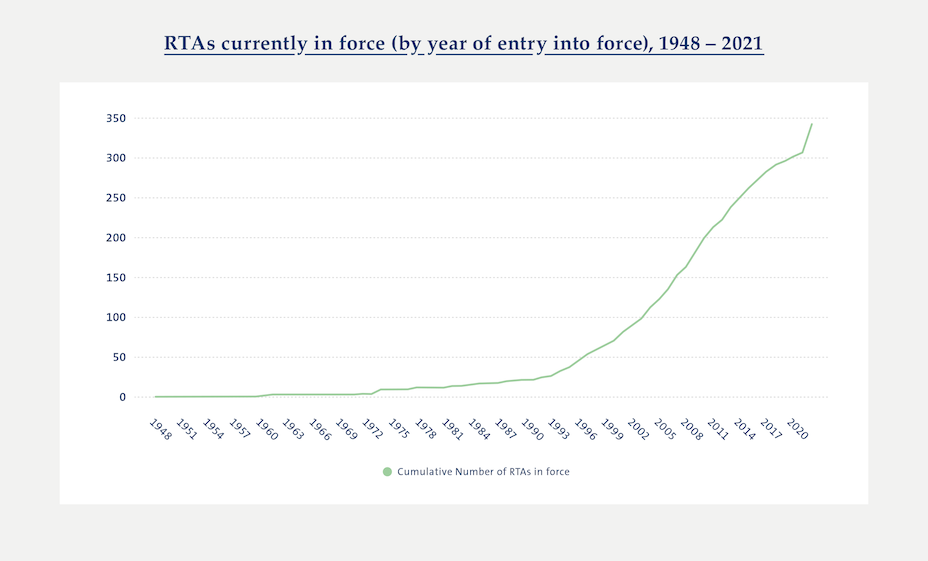

Second, most trade negotiations now occur in the context of regional trade agreements (RTAs), which have proliferated since the creation of the WTO. While RTAs as such are often worthwhile initiatives, their proliferation is a clear testament to the waning importance of the WTO as the main forum for international trade policy cooperation. Since the establishment of the WTO, RTAs have risen in number, reaching 338 agreements notified as of December 2020. All 164 WTO Members are party to at least one RTA.

RTA proliferation is a clear testament to the WTO’s waning importance as the main forum for international trade policy cooperation

Besides undermining the WTO as a negotiation forum, there are additional concerns about the proliferation of RTAs. One concern is that they are inherently discriminatory and might even be purposefully designed to exclude or isolate specific countries. Another concern is that their chosen approach to deep integration is sometimes viewed as biased towards the interests of multinational corporations, particularly in the areas of regulation, investment, and intellectual property rights. The latter concern was also at the heart of the strong public opposition to recently negotiated mega-RTAs like the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between the EU and Canada or the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the EU and the US.

On the other hand, RTAs can clearly also be a major force for good in the world trading system. Most obviously, they contribute substantially to further shallow integration by eliminating tariffs between member countries. Moreover, they are often the only realistic avenue to pursue significant deep integration, which requires the coordination of sensitive behind-the-border policies like health and safety standards.

Ill-timed crises

On top of these major challenges, the WTO has faced multiple additional crises over the course of the last few years. What comes to mind immediately are the breakdown of trade policy cooperation during the China-US trade war and the COVID-19 pandemic, which severely damaged the credibility of the WTO as a guarantor of stable trade relations. We have extensively discussed the trade-implications of the Covid-19 pandemic in our previous two Kühne Impact Series and will therefore not further belabor this point here.2

The WTO has faced multiple additional crises over the course of the last few years.

Another crisis pertains to the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Mechanism (DSM), and more precisely to its Appellate Body (AB). The DSM was often referred to as the “crown jewel” of the organization. Over the past two decades, it has been remarkably active: since its inception, 600 disputes have been initiated by WTO members. And the high rate of compliance with the decisions testified to the system’s success. With time, while the dynamics of trade relationships evolved and deepened significantly, the rules and procedures of the system have not followed these developments, due to the inactivity on the legislative front. This effectively forced the DSM and the AB to make law by their rulings. As a consequence, the dispute settlement mechanism entered a deep crisis of legitimacy due to its judicial overreach. The system collapsed in December of 2019, when the United States refused to appoint new members to the AB.

A new hope

In the midst of the pandemic, on May 14, 2020, the WTO Director-General (DG) Roberto Azevêdo announced that he would step down, cutting his second term short by one year and leaving the damaged organization leaderless. The appointment of the new DG required a consensus of the 164 member countries; that was not reached until Biden became US President, and Yoo Myung-hee – the candidate backed by the US – announced her withdrawal from the race. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala was then appointed DG, making history as first woman and first African at the head of the WTO.

DG Okonjo-Iweala faces a monumental task. In her first public statement, she outlined her political agenda and vision for the WTO for the months and years to come, in order to “restore and rebrand the WTO as a key pillar of global economic governance, a force for a strong, transparent, and fair multilateral trading system, and an instrument for inclusive economic growth and sustainable development”.3

WTO Director-General Okonjo-Iweala faces a monumental task.

Her first point is to tackle the pandemic by intensifying international cooperation to fight COVID-19. The WTO should play a more forceful role in exercising its monitoring function and encouraging members to minimize and remove export restrictions and prohibitions that hinder supply chains for medical goods and equipment (according to the International Trade Centre, 100 countries still maintain export restrictions and prohibitions on this front).

Her second objective is to discuss the structural reforms that the WTO needs. In order to restore credibility in the organization, the newly appointed DG wants to deliver early successes and results. DG Okonjo-Iweala hopes to finalize the fisheries subsidies negotiations ahead of the 12th Ministerial Conference. She could capitalize on an “easy” win and get momentum for the more challenging reforms that the WTO needs. In her statement, she highlighted the need of reinstating and reforming the dispute settlement mechanism, creating a system that “can garner the confidence of all, including small developing and least developed countries who have found it challenging to utilize”.4

Another point of her agenda is to update the WTO rulebook. The rules lag behind those of several RTAs, which contributes to countries’ preference for RTAs in the first place. The starting point will be to take account of 21st century realities such as e-commerce and the digital economy.

A final important point highlighted in her speech relates to the environment. DG Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala plans to direct the WTO in supporting the green and circular economy, in reactivating the negotiations on environmental goods and services, and addressing more broadly the nexus between trade and climate change. The focus on climate change is quite new within the WTO, but it is less surprising that she mentioned it in her first remarks as DG. Among all the candidates for the position, Dr. Okonjo-Iweala was the most outspoken about the environment, even though it is not a prominent area of ongoing WTO negotiations.5 One might expect that she will be favorable to the EU’s proposed carbon tax as well as tariffs removal on renewable energy technology and services, also in light of the fact that the EU was a strong supporter of her candidacy.

Concluding remarks

While life has never been easy for the WTO, its crisis took on existential proportions during the past few years. It hit rock bottom when President Trump publicly entertained the idea of withdrawing from the organization, a blow it would most likely not have survived.

Relative to this dire situation, things have already much improved. Most importantly, the WTO was able to appoint a distinguished new leader with an ambitious reform agenda with the support of the new US administration.

Having said this, WTO reform is a monumental challenge and one might understandably argue that Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala’s agenda is highly incomplete. But, as is known, politics is the art of the possible and we view her agenda as a promising starting point.

- The WTO at 25: A message from the Director-General Roberto Azevêdo

- “Pandemic and Trade: The Dynamics of Global Trade in Times of Corona”, Kühne Impact Series 3-20 and “Crumbling Economy, Booming Trade: The Surprising Resilience of World Trade in 2020”, Kühne Impact Series 01-21.

- Statement of the Director-General Elect Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala to the Special Session of the WTO General Council, 15 February 2021 (JOB/GC/250)

- Ibid.

- Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala used her written candidate statement to the WTO to call on the organization to take on “fresh challenges, such as ensuring optima lcomplementarity between trade and the environment”.

More Issues

Variable Carbon Pricing and the Environmental Gains from Trade

Optimal Carbon Tax for Maritime Shipping?

The Global Diffusion of Clean Technology

The Sustainable Globalization Index

The Distributional Effects of Carbon Pricing:

The Green Comparative Advantage:

Global Trade

The EU Emissions Trading System

The Hidden Green Sourcing Potential in European Trade

The European Green Deal

Post-COVID19 resilience

Africa’s Trade Potential

Buy Green not Local

Crumbling Economy, Booming Trade

Pandemic and Trade

The Dynamics of Global Trade in Times of Corona

EU Trade Agreements

Past, present, and future developments