Impact Series: 04–21

Africa’s Trade Potential:

Escaping the Colonial Past by

Building a Self-Sustaining Future

Outline

Africa accounts today for 17% of the world’s population, but less than 3% of global GDP. With a fast-growing population, the continent is projected to reach 4.3 billion inhabitants (39% of the world’s total) by the end of the century. This big domestic market could represent a significant opportunity, but the economy of the continent is not growing at the same pace. In fact, Africa is still struggling to overcome its colonial past, and to gain from its current (new-colonial) dependency from China. The consequences of this can be seen in the extremely low share of intra-African trade and the underdeveloped within-continent infrastructure network. The newly implemented African Continent Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) could prove to be a pivotal step forward, paving the way for self-sustaining economic growth and long-lasting social and geo-political stability on the African continent.

An economic and geo-political outlook

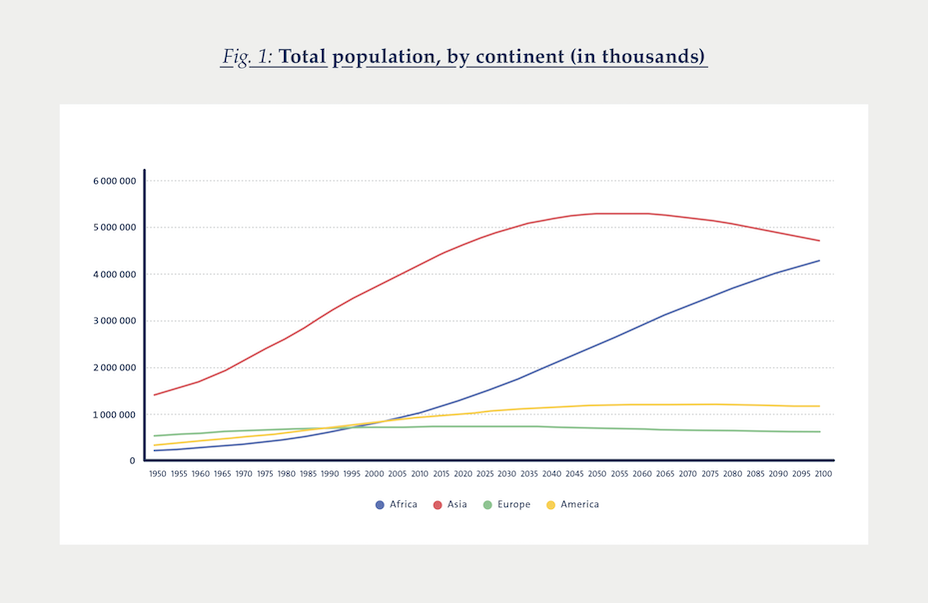

The African continent is characterized by deep demographic and economic heterogeneity. Taken as a whole, it counts more than 1.34 billion inhabitants, or 17% of world’s population, making it the second most populous continent. It is also the fastest growing continent (Figure 1): with a growth rate of more than 2.5% per year, total population in Africa is projected to reach 4.3 billion (and almost 40% of world’s total) by the end of the century. Nigeria – Africa’s most populous country – has now 200 million inhabitants and occupies the 7th position in the world ranking. The country is expected to quadruple its population by 2100, and to become the second most populous country in the world, second only to India.

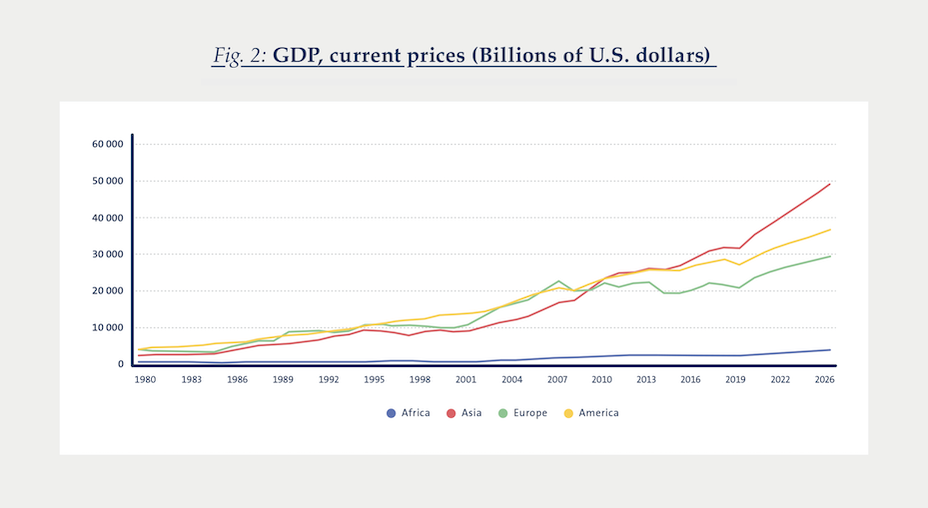

The big domestic market could represent a significant opportunity for economic growth. Nevertheless, the continent is facing challenges in realizing its full potential. There are significant economic development gaps both between Africa and the rest of the world, as well as among African countries. These gaps, rather than narrowing, are constantly increasing. Looking at the evolution of GDP over time (Figure 2), it is evident that this divergence is widening steadily.

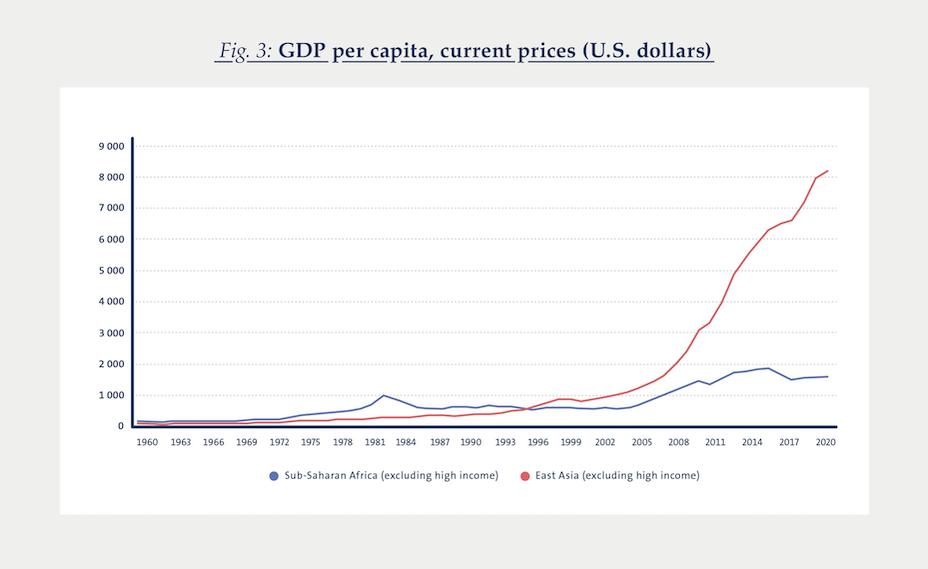

Even when compared to emerging economies, Africa is lagging behind in terms of economic development and poverty reduction. This can be seen also in terms of GDP per capita (Figure 3): from the 60s till mid-90s sub-Saharan Africa had a higher GDP per capita than East Asia, now East Asia’s GDP per capita is more than 5 times larger than the sub-Saharan African one. Moreover, poverty is still extremely widespread in Africa where 32 out of 48 Least-Developed Countries are located.

Africa is lagging behind in terms of economic development and poverty eduction.

In today’s dominant discourse, the development trajectory of many sub-Saharan African countries is considered a failure, whereas that of East Asian countries is pictured as a success.

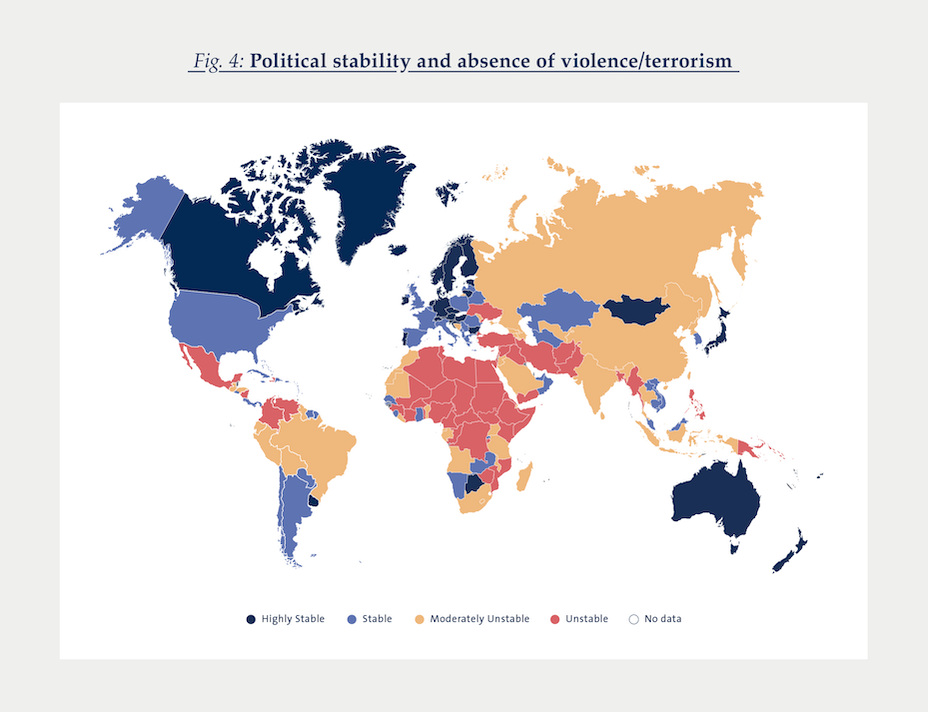

One of the main explanations for this divergence is to be found in the colonial past of Africa, which still has severe repercussions today. One of the main longterm outcomes is the deep social and political instability of the region. African countries are among the most unstable in the world (Figure 4). According to the Fragile State Index produced by the Fund for Peace – which uses a 12 factors system to determine the rating of each nation, including security threats, economic implosion, human rights violations and refugee flows – nineteen of the twenty-five most fragile states are in Africa.1

African countries are among the most unstable in the world.

The economic effects of the colonization era, of the unsuccessful decolonization, and of the political instability of the continent can be easily seen by analyzing the actual African patterns of trade.

Africa is lagging behind in terms of economic development and poverty eduction.

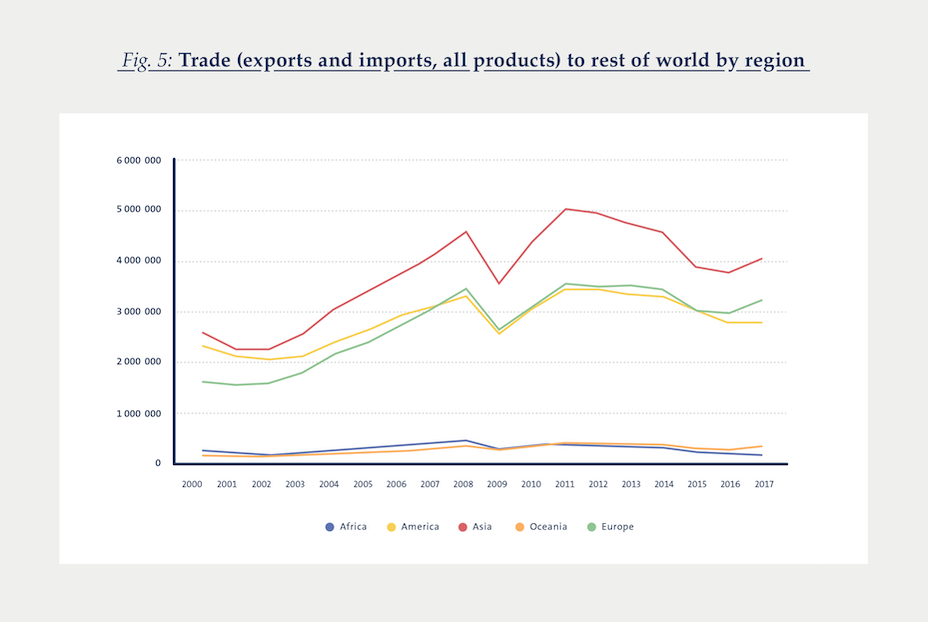

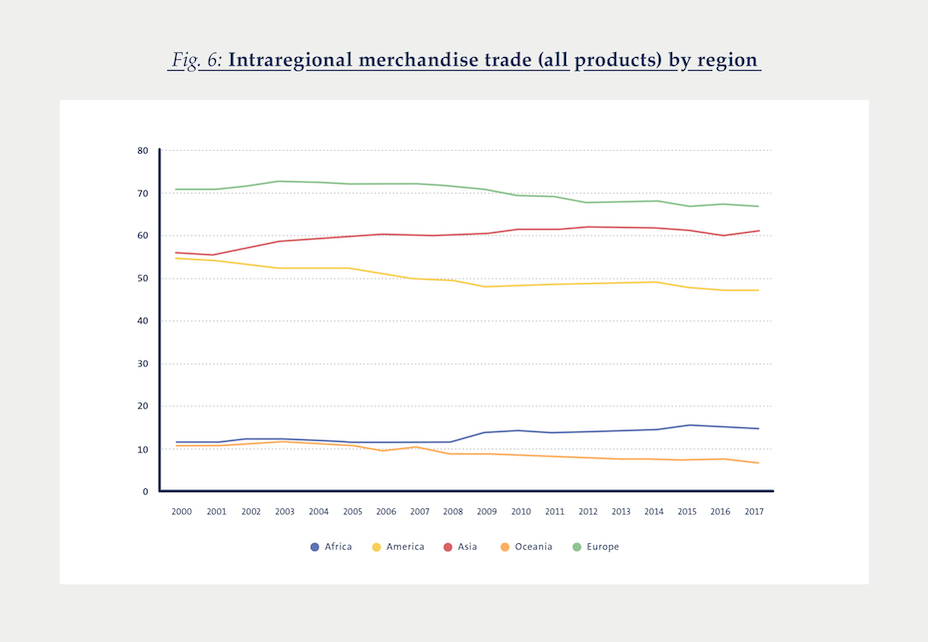

Africa is a marginal player in global trade (Figure 5). Total trade from Africa to the rest of the world averaged $760,463 million in current prices in the period 2015–2017, compared with $481,081 million from Oceania, $4,109,131 million from Europe, $5,139,649 million from America, and $6,801,474 million from Asia.2 Even with this low share of participation to global trade, Africa depends heavily on trade with the rest of the world, making the continent extremely vulnerable to external trade shocks. More concretely, the share of exports from Africa to the rest of the world ranged from 80 to 90 percent in 2000–2017. The only other region with a higher export dependence on the rest of the world is Oceania. Conversely, the share of intraregional exports in total exports is lowest in Africa, compared with other regions. Intra-African exports were 16.6 per cent of total exports in 2017, compared with 68.1 percent in Europe, 59.4 percent in Asia, 55.0 per- cent in America.3 On the bright side, Africa, along with Asia, is the only region with a rising trend in intra-regional trade from 2008 (Figure 6). A boost in regional trade is crucial to help Africa reduce its vulnerability to external trade shocks.

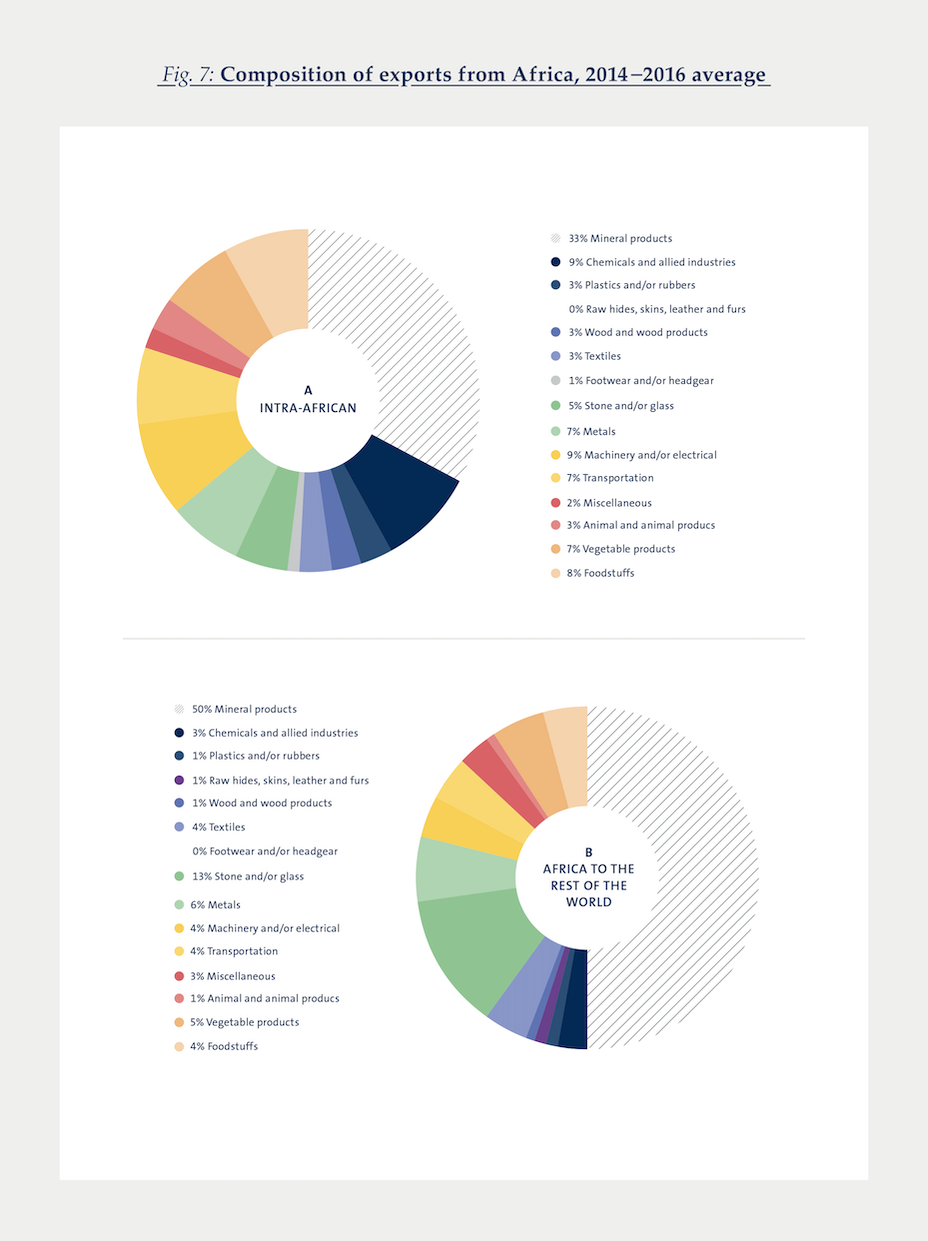

With regards to the product and sectoral composition of intra-African trade, even if the continental market remains limited in size, intraregional exports appear to be more diversified and less primary commodity-dependent than exports from Africa to the rest of the world (Figure 7).

Africa depends heavily on trade with the rest of the world, making the continent extremely vulnerable to external trade shocks.

Mineral products account for one third of intra-African exports and constitute half of total exports from Africa to the rest of the world. At the aggregate level, in 2015–2017, exports of manufactures accounted for 45 per cent of intra-African exports, but only 20 per cent of exports from Africa to the rest of the world.

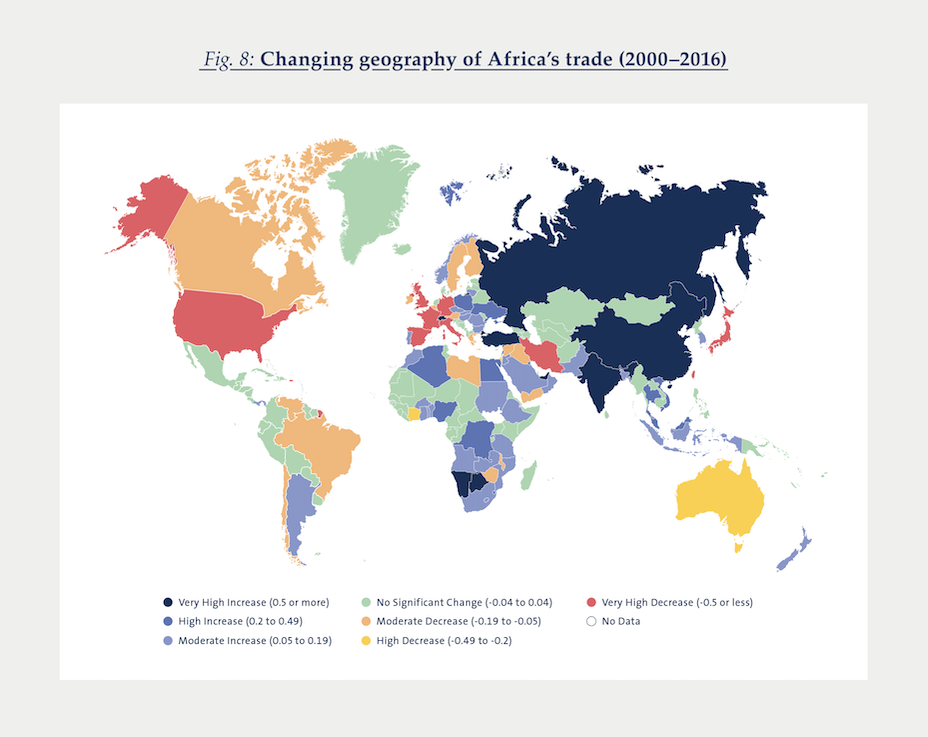

The other important trend in African trade is the sharp growth of trade with Asia, and more specifically with China. The geographical location of Africa’s main trading partners has been changing since 2000. While many countries in Africa and Asia are capturing bigger shares, some countries in Europe, North America, Australia and parts of South America experience generally declining shares (Figure 8).

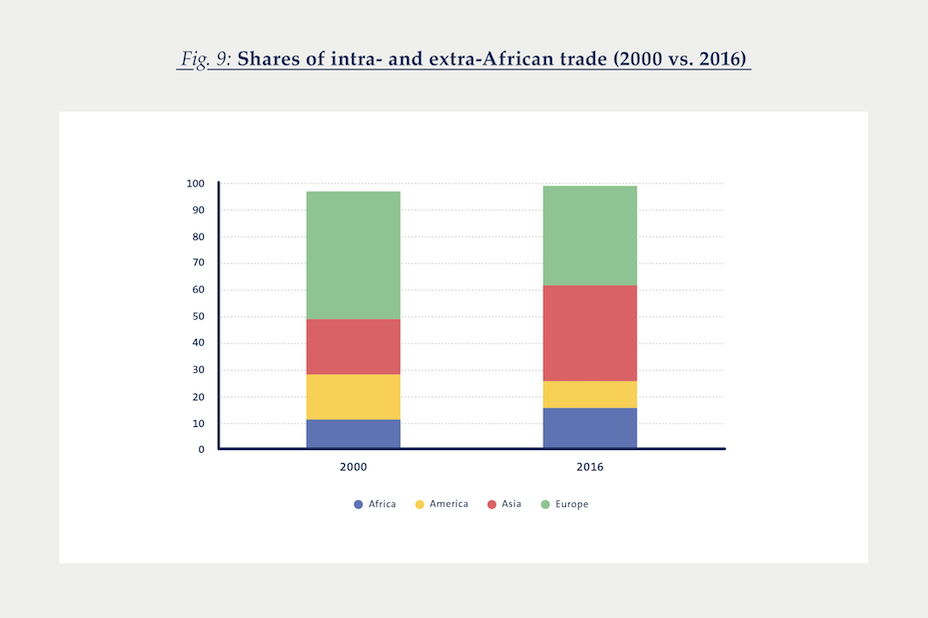

All of these trends are visually summarized in Figure 9, which illustrates the importance of trade between Africa and other regions. Europe is still the biggest trading partner for Africa, but its central role has been eroded by the increasing importance of Asia.

Some of these trends can be explained also in light of the extremely underdeveloped infrastructure network of the African continent. In fact, the deficiencies in transport infrastructure partly led to the low trade levels within the continent, and are still one of the biggest obstacles in reverting this trend. Moreover, the existing continent’s infrastructure was purpose-built for the colonial export of raw materials — and little has changed since African nations achieved independence beginning in the 1950s.

The network across Africa, including long-distance and regional, is still of extremely low density and poor quality, although the situation varies considerably across countries. While road is the main mode of transport, carrying 90% of passengers and 80% of goods, more than 50% of roads are still unpaved.

Less than half the population has access to all-season roads, which includes urban and smallscale roads. This issue is exacerbated by vehicle overloading and inefficient road maintenance, particularly in least developed countries.

In the last decades, China played a key role in building the infrastructure network of the continent, and its predominance is fast increasing. The Infrastructure Consortium for Africa estimated that in 2018 China contributed $25.7 billion of the overall $100.8 billion committed toward African infrastructure development projects. A 2017 McKinsey report estimated that Chinese construction enterprises won almost half of all engineering, procurement, and construction contracts continentwide — including those funded by non-Chinese sources like the World Bank.

Most of the projects are in the Transport, Shipping and Ports sectors (52.8%), followed by Energy and Power (17.6%), Real Estate (14.3%, including industrial, commercial, and residential), and Mining (7.7%). China’s emphasis on infrastructure construction increased with the launching of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

As of April 2020, 42 out of 54 African countries have signed agreements with China to be part of it. Looking at the data, is seems that there are very few alternatives for Africa to finance its infrastructures. The EU for example, despite being (still) the continent’s biggest trade partner, funded only 6% of African infrastructures in 2019, while China funded 20.8% of them.4

However, in recent years, concerns have been raised about the proliferation of Chinese involvement in Africa. Academics, policymakers, and other observers have stressed the risk of a new wave of colonialism in Africa: Chinese investments in the continent could result in a “debt-trap diplomacy” i.e., the way for China to increase its leverage over Africa through enormous debt.

AfCFTA: The potential for a self-sustained growth for Africa

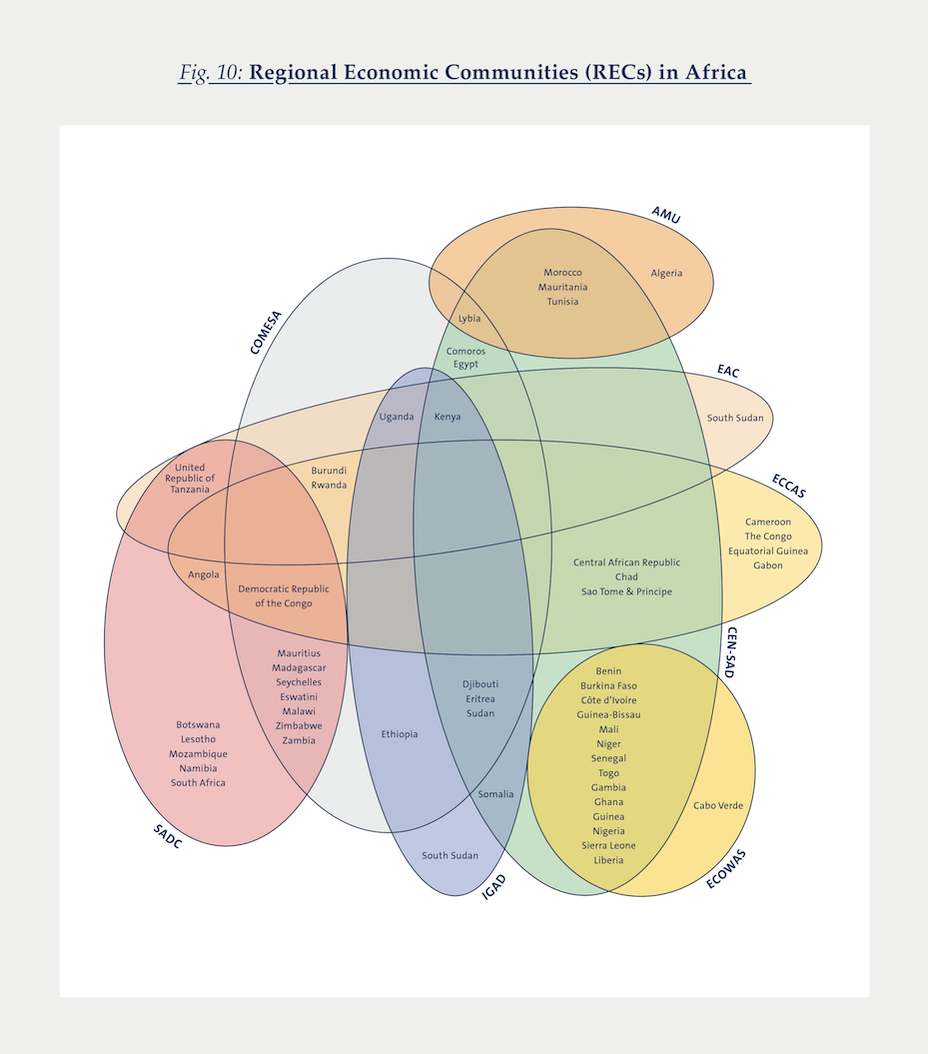

There is still potential for Africa to escape its colonial past and its increasing (new-colonial) dependence to China. This could happen mainly by exploiting the big potential of the booming African domestic market. So far, one of the main difficulties of the continent is still related to the fact that the markets are small, fractured, and partly isolated. After gaining independence, many African countries attempted to foster economic development by establishing several Regional Economic Communities (REC), or by exploiting cross-border agreements that existed even during the colonial period. These attempts have been just partially successful. Nowadays there are eight Regional Economic Communities (RECs) that are recognized as the building blocks of the African Economic Communities by the 1991 Abuja Treaty.5 However, several RECs have overlapping memberships and seem to complicate instead of facilitating trade relationships among the African countries. Figure 10 gives a visual representation of the extent through which these regional agreements overlap among themselves. It is crucial to unify the trade regime across the continent in order to promote the flow of goods and services within the African borders.

There is still potential for Africa to escape its colonial past.

The newly commenced African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) could represent the right step forward to tackle all of these challenges, and the numerous failed attempts to escape economic stagnation. The agreement was first signed on March 21, 2018 by 44 of the 55 African countries.6 While this represented a huge success, there were two notable holdouts: Nigeria and South Africa, the two largest economies in Africa. Following several additional rounds of negotiations, as of July 2019, 54 of the 55 African Union states had signed the agreement, with Eritrea the only country not signing it. After months of delay because of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa, the AfCFTA officially (but largely symbolically) launched on January 1, 2021. The free-trade area is the largest in the world in terms of the number of participating countries since the formation of the World Trade Organization.

The AfCFTA free-trade area is the largest in the world in terms of the number of participating countries since the formation of the WTO.

The trade agreement has ambitious long-term goals of deepening integration among African Union member States and building a prosperous and united Africa. Among the main objectives of the AfCFTA are the facilitation, harmonization, and better coordination of trade regimes as well as the elimination of challenges associated with multiple and overlapping trade agreements across the continent. Through this agreement, African economies hope to strengthen the competitiveness of the local industries, realise economies of scale for domestic producers, better allocate resources, and attract foreign direct investments. The Phase I of the agreement, which covers goods and services liberalization, was negotiated in 2018 at the Kigali summit. Negotiations for Phase II began in February 2019. These negotiations will cover protocols for competition, intellectual property, and investment. The agreement requires members to remove tariffs from 90% of goods (each nation is permitted to exclude 3% of goods from this agreement), allowing free access to commodities, goods, and services across the continent. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa estimates that the agreement will boost intra-African trade by 52 percent.

The AfCFTA represents an unprecedented opportunity to address high tariffs and trade costs across these regional economic communities, and to boost intra-African trade and hence benefit from regional integration. This agreement could prove to be a pivotal step forward, paving the way for self-sustaining economic growth and long-lasting social and geo-political stability on the African continent.

- These are (in order of fragility): Somalia, South Sudan, DR Congo, Central African Republic, Chad, Sudan, Zimbabwe, Burundi, Cameroon, Nigeria, Guinea, Mali, Eritrea, Niger, Libya, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Uganda, Congo.

- UNCTAD calculations, based on the UNCTADstat database.

- Ibid.

- Deloitte, “Africa Construction Trends Report 2019”

- These are: Arab Maghreb Union (AMU/UMA), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), East African Community (EAC), Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), Southern African Development Community (SADC), Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), and Community of Sahel-Saharan

States (CEN-SAD). - This number includes the partially recognized Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (or Western Sahara).

More Issues

Variable Carbon Pricing and the Environmental Gains from Trade

Optimal Carbon Tax for Maritime Shipping?

The Global Diffusion of Clean Technology

The Sustainable Globalization Index

The Distributional Effects of Carbon Pricing:

The Green Comparative Advantage:

Global Trade

The EU Emissions Trading System

The Hidden Green Sourcing Potential in European Trade

The European Green Deal

Post-COVID19 resilience

Buy Green not Local

A New Hope for the WTO?

Crumbling Economy, Booming Trade

Pandemic and Trade

The Dynamics of Global Trade in Times of Corona

EU Trade Agreements

Past, present, and future developments