Impact Series: 05–21

Post-COVID19 resilience:

Lessons from the China Trade Shock for Europeʼs economies

Outline

When we talk about the economic consequences of COVID-19, the question arises about the strength and duration of the changes triggered by the pandemic. Currently, all indications are that COVID-19 is likely to change the structure of the world economy permanently. Evidence suggests that the pandemic is a permanent reallocation shock – one that cannot be mitigated with standard fiscal and monetary stimulus. What are the structural reforms and mechanisms that would allow economies to adapt and to effectively reallocate resources in response to such shocks? Which features made economies resilient to major reallocation shocks in the past? To answer these questions, we take a closer look at the China Trade Shock and its impact on the US economy. We then draw lessons for Europe today.

COVID-19 is likely to change the structure of the world economy permanently. Barrero, Bloom, and Davis (2020a, 2020b) provide evidence that the pandemic is a permanent reallocation shock in the sense that shifts in working arrangements, consumer spending patterns, and business practices induced by the pandemic will not fully reverse. This reallocation started long before the pandemic but has clearly been accelerated by it. Pagano, Wagner, and Zechner (2020a, 2020b) show that stocks of firms in sectors that are resilient to social distancing outperformed less resilient stocks particularly strongly during the COVID-19 pandemic but that this outperformance predates the pandemic by several years. Carstens (2020) argues that standard fiscal and monetary stimulus will not be sufficient to deal with this “great reallocation”. Rather, the optimal policy requires structural reforms and mechanisms that would allow economies to adapt and to effectively reallocate resources in response to such shocks.

Against this backdrop, it seems natural to ask which features made economies resilient to major reallocation shocks in the past. One such shock is the so-called China trade shock (CTS). Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (2013) show that US labor market regions with manufacturing industries, which were particularly exposed to competition from cheaper Chinese imports, also experienced the biggest decline in manufacturing employment and wages between 1991 and 2007.

The labor market effects of asymmetric trade shocks are regionally concentrated and persistent because the geographical mobility of labor is generally quite limited (Faber, Sarto, and Tabellini (2019; Notowidigdo 2020; Blanchard and Katz 1992)). In the absence of labor mobility, the mobility of capital should therefore play a particularly prominent role for the adjustment to asymmetric shocks in a monetary union (Mundell (1961)).

In a recent paper (Hoffmann and Ruslanova 2021), we examine how differences in financial integration across local economies (states and commuting zones) in the United States affected sectoral reallocation after the CTS. To capture local financial integration, we exploit the wave of state-level banking deregulation that swept through the US from the 1970’s until the early 1990’s. Since states deregulated in different years (Kroszner and Strahan 1999), there was considerable variation at the state level in the degree of banking liberalization until local economies were hit by the CTS in the early 1990’s. More specifically, states that opened their banking markets for out-of-state banks earlier had a stronger presence of countrywide banks and ‒ as we show ‒ a more elastic supply of bank credit to households. We develop a simple model of a small open economy with housing and a tradable sector (manufacturing) to argue that banking integration facilitates and speeds up the reallocation between these two sectors after manufacturing is hit by a terms of trade shock (i.e. the CTS). In our model, this happens because financial integration allows households to smooth consumption which stabilizes their demand for the non-tradable good (housing). This in turn stabilizes housing prices and wages in the housing sector. Given the shock to manufacturing, higher house prices (and therefore: a higher marginal product of labor in the housing sector) speeds up reallocation of labor away from the import-exposed manufacturing sector towards the housing sector.

Banking integration facilitates and speeds up the reallocation between housing and manufacturing after manufacturing is hit by a terms of trade shock

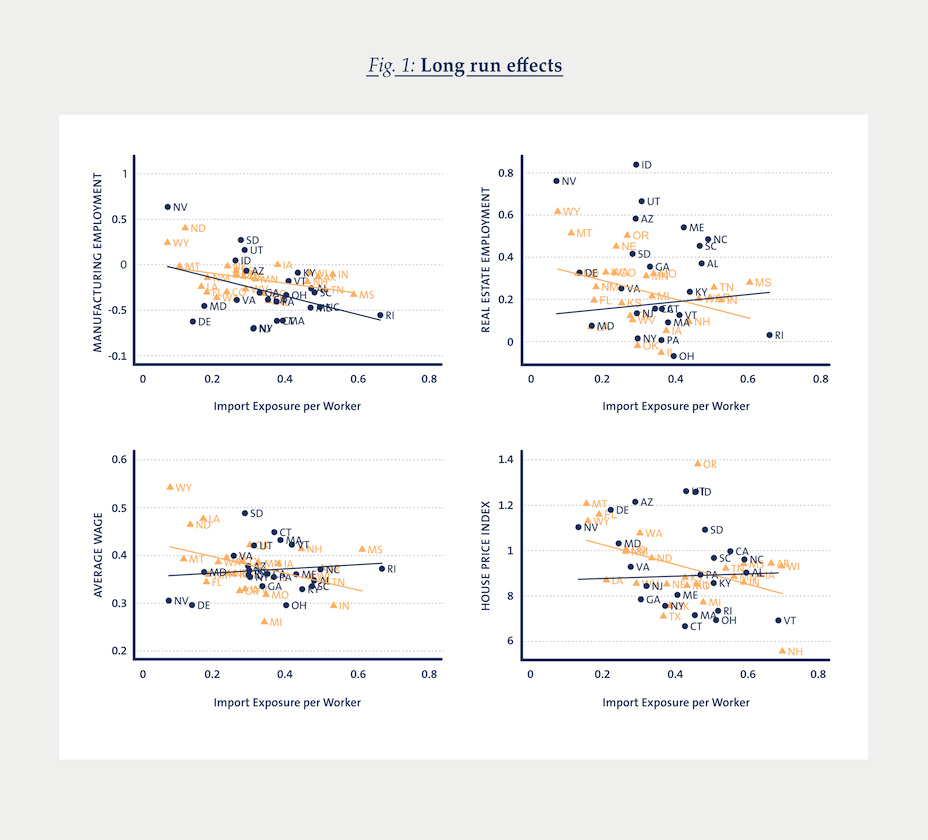

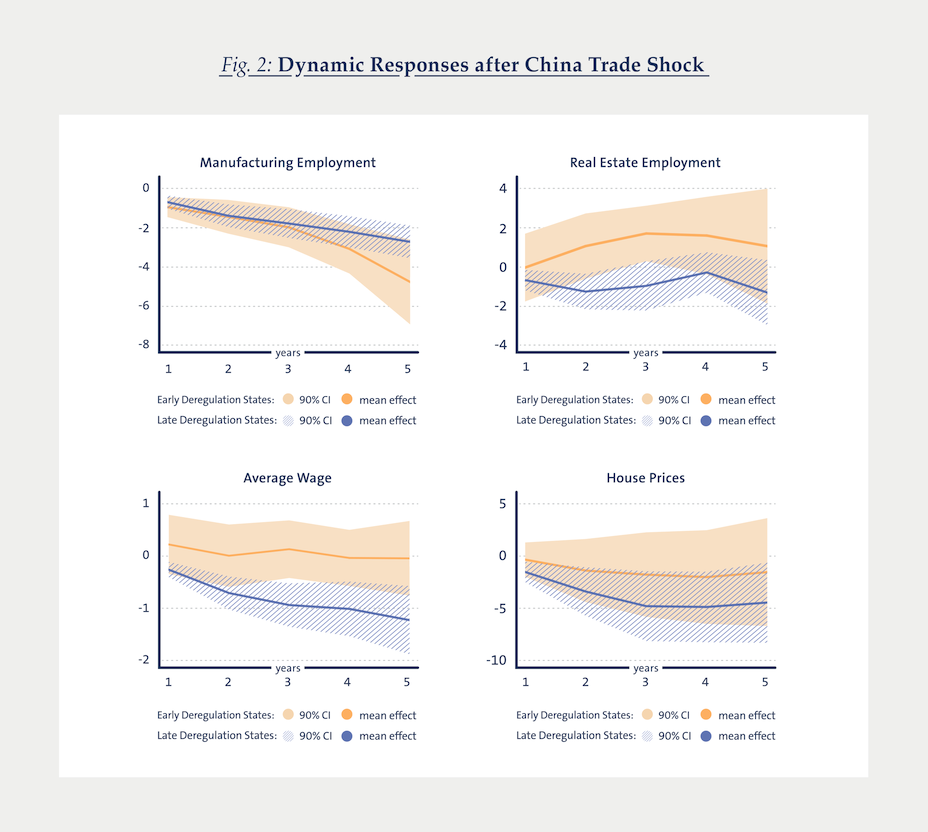

Our empirical results ‒ summarized in Figure 1 and 2 ‒ line up with these predictions. We classify states into two groups: early liberalizers are states that opened their banking markets for banks from other states before 1985 and are therefore relatively more financially integrated. Conversely, states that opened their banking markets only after 1985 are classified as late liberalizers.

As is apparent from the regression lines, a given increase in import exposure over 1991-2007 generally leads to bigger decline in wage, real estate employment and house price growth for late deregulation states than for early-deregulation states (the orange regression line is falling more steeply while the blue line is flat or increasing). However, a given increase in import exposure generally decreases the manufacturing share more for early-deregulation states (the blue regression line is falling more steeply). This suggests that early deregulation (i.e. financial openess) not only shields a state’s wider economy (housing and real estate markets, general wage growth) from the impact of import competition in manufacturing. It actually seems to ease reallocation of labor — early deregulation is associated with a stronger decline in manufacturing and a stronger increase in real-estate related employment.

While Figure 1 emphasizes the long-run differences between the two groups, Figure 2 shows estimates of the dynamic responses of different variables to the CTS. The upshot of the two figures is the same: For a given exposure to Chinese imports financially more open local economies saw a swifter reallocation of labor from the import-exposed manufacturing sector into the non-tradable (housing) sector, with more pronounced declines in the manufacturing employment but lower declines in the real estate employment. Thus, financial integration spurred reallocation in financially integrated states while in late-liberalized states the ailing manufacturing sector declined more slowly ‒ at the expense of overall employment. Consistent with the mechanism in our model, wages and non-tradable prices, in particular housing prices, remained relatively stable in financially more open states. Analogous results also hold for the growth rates of state average income and consumption per capita. Household’s ability to borrow in order to smooth consumption is key for reallocation because it keeps demand for housing and house prices up. Consistent with this prediction, we see that household borrowing increased more in financially integrated states.

In the paper, we further corroborate our findings on commuting-zone level data. In addition, we provide bank-county level evidence based on the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data base. This evidence shows that geographically integrated banks played a crucial role in accommodating the additional credit demand of households that was induced by their desire to smooth consumption after the CTS.

Financial integration spurred reallocation in financially integrated states while in late-liberalized states the failing manufacturing sector declined more slowly – at the expense of overall employment.

Summary

Our results hold some lessons for European policymakers in the post-pandemic world. The effects of the pandemic reallocation shock will be very uneven within ‒ and even more so between ‒ member countries of the European Monetary Union (EMU). Labor mobility and capital mobility should both be important adjustment mechanisms. However, labor mobility in Europe remains much lower than in the United States (House, Proebsting, and Tesar 2018), while banking and capital market union ‒ the major European projects of financial integration in the last decade ‒ also remain woefully incomplete. The lack of genuine cross-border banking integration in the European Monetary Union (EMU) has long been identified as a prime reason for why risk sharing among EMU countries is so low and generally not resilient during major crises (Draghi 2018; Hoffmann et al. 2019a, 2019b). Our results show that access to finance for firms and in particular for households will be key to ease the great reallocation along. But Europe still does not have an integrated retail banking market. Completing the banking union while moving forward on capital markets union will therefore be crucial in making the EMU resilient against the challenges of the reallocation triggered by the COVID-19 shock and to similar shocks in the future. The risk sharing mechanisms in the EMU so far have been surprisingly resilient during the current crisis (Giovannini, Horn, and Mongelli 2021). But Europe’s experience from the great financial crisis of the previous decade shows that we should not take this for granted

- Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States.”American Economic Review 103 (6): 2121–68.

https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.6.2121 - Barrero, Jose Maria, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven Davis. 2020a. “COVID-19 and Labour Reallocation: Evidence from the Us.” VoxEU.org, 14 July.

- Barrero, Jose Maria, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis. 2020b. “COVID-19 Is Also a Reallocation Shock.” University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2020-59.

https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3592953 - Blanchard, Olivier, and Lawrence Katz. 1992. “Regional Evolutions.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 23 (1): 1–76.

https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:bin:bpeajo:v:23:y:1992:i:1992-1:p:1-76 - Carstens, Agustin. 2020. “The Great Reallocation.”

https://www.bis.org/speeches/sp201013.htm - Draghi, Mario. 2018. “Risk-Reducing and Risk-Sharing in Our Monetary Union.”

https://www.bis.org/review/r180516a.htm - Faber, Marius, Andres Sarto, and Marco Tabellini. 2019. “The Impact of Technology and Trade on Migration: Evidence from the Us.” Harvard Business School BGIE Unit Working Paper No. 20-071.

- Giovannini, Alessandro, Carl-Wolfram Horn, and Francesco Paolo Mongelli. 2021. “An Early View on Euro Area Risk-Sharing During the Covid-19 Crisis.” VoxEU.org, 10 January.

https://voxeu.org/article/early-view-euro-area-risk-sharing-during-covid-19-crisis - Hoffmann, Mathias, Egor Maslov, Bent E. Sorensen, and Iryna Stewen. 2019a. “Banking Integration in the Emu: Let’s Get Real!” VoxEU.org, 10 January.

- Hoffmann, Mathias, Egor Maslov, Bent E. Sorensen, and Iryna Stewen. 2019b. “Channels of Risk Sharing in the Eurozone: What Can Banking and Capital Market Union Achieve?” IMF Economic Review 67 (3): 443–95.

https://doi.org/10.1057/s41308-019-00083-3 - Hoffmann, Mathias, and Lilia Ruslanova. 2021. “Softening the Blow: U.S. State-Level Banking Deregulation and Sectoral Reallocation after the China Trade Shock.” University of Zurich Economics Discussion Paper no 365

https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-190445 ; University of Zurich. - House, Christopher, Christian Proebsting, and Linda Tesar. 2018. “Quantifying the Benefits of Labor Mobility in a Currency Union.” National Bureau of Economic Research; National Bureau of Economic Research.

https://doi.org/10.3386/w25347 - Kroszner, R. S., and P. E. Strahan. 1999. “What Drives Deregulation? Economics and Politics of the Relaxation of Bank Branching Restrictions.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 114 (4): 1437–67.

https://doi.org/10.1162/003355399556223 - Mundell, Robert A. 1961. “A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas.” The American Economic Review 51 (4): 657–65.http://www.jstor.org/stable/1812792

- Notowidigdo, Matthew J. 2020. “The Incidence of Local Labor Demand Shocks.” Journal of Labor Economics 38 (3): 687–725.

https://doi.org/10.1086/706048 - Pagano, Marco, Christian Wagner, and Josef Zechner. 2020a. “COVID-19, Asset Prices, and the Great Reallocation.” VoxEU.org, 11 June.

- Pagano, Marco, Christian Wagner, and Josef Zechner. 2020b. “Disaster Resilience and Asset Prices.” CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14773.

https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3603666

More Issues

Optimal Carbon Tax for Maritime Shipping?

The Global Diffusion of Clean Technology

The Sustainable Globalization Index

The Distributional Effects of Carbon Pricing:

The Green Comparative Advantage:

Global Trade

The EU Emissions Trading System

The Hidden Green Sourcing Potential in European Trade

The European Green Deal

Africa’s Trade Potential

Buy Green not Local

A New Hope for the WTO?

Crumbling Economy, Booming Trade

Pandemic and Trade

The Dynamics of Global Trade in Times of Corona

EU Trade Agreements

Past, present, and future developments