Outline

Adopting clean energy technology is crucial for reducing emissions and achieving global climate goals. In this Kühne Impact Series, we shed light on the importance of global diffusion of clean technology through international trade. In particular, we highlight China’s expansion in the solar energy sector and its role in bringing down the cost of solar energy worldwide. Our main result is that international trade and globally integrated value chains have dramatically reduced the global average cost of renewable technologies. Keeping markets open to trade is essential for enabling a low-carbon energy transition as it ensures that all countries benefit from the lower cost of clean energy technologies. Moreover, we highlight three potential challenges that represent considerable vulnerabilities for the global diffusion of clean technology: (i) the current geographical concentration in global supply chains, (ii) the US-China and EU-China “Solar Trade War,” and (iii) the global slowdown in highquality solar energy inventions.

Solar Energy is Booming Globally ...

Climate change is already negatively affecting the environment with severe consequences for many societies around the world.1 To mitigate climate change, greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced. With around 76% of global greenhouse gas emissions coming from energy production and use, the decarbonization of energy is the most important element of the green transition.2 The good news is that over the past two decades, the proportion of global energy generated from renewable technologies has experienced a remarkable and swift expansion. In 2022, the renewable share of the total electricity generation capacity rose to 40%. In fact the vast majority of new capacity built is in renewables: the share of renewables in new electricity capacity reached 80% in 2022 compared to 20% in 2002.3

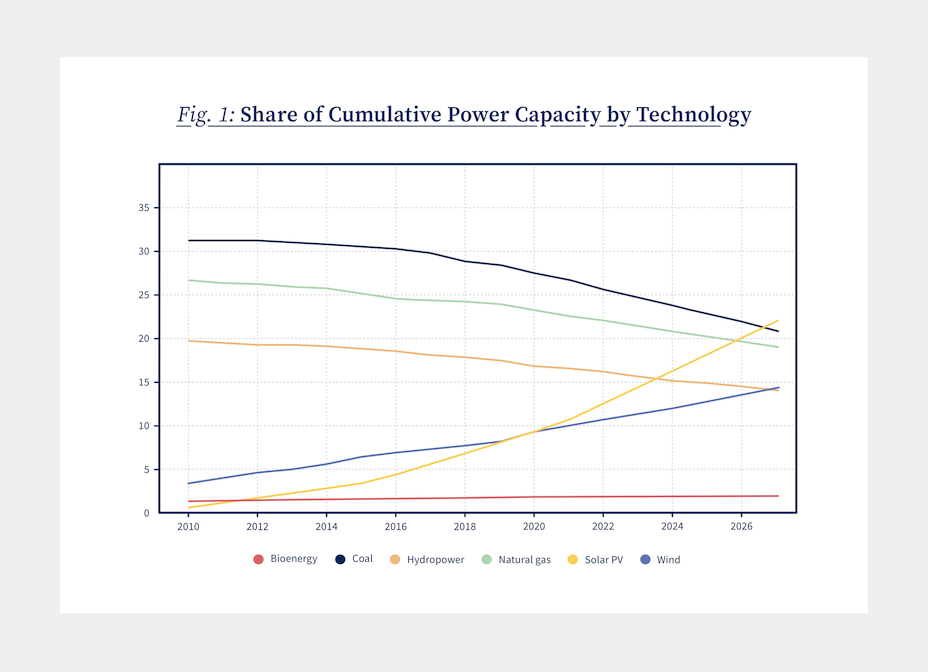

Much of the increased capacity of renewable technologies comes from solar photovoltaic (PV) technologies.3 Figure 1 illustrates this development by showing the share of cumulative power capacity by technology over time. The figure includes a forecast made by the International Energy Agency for the period after 2022. In 2022, solar PV constituted about 13% of electricity generation capacity, and the International Energy Agency anticipates solar PV’s installed power capacity to almost triple by 2027. This development would imply that solar PV capacity exceeds hydropower, natural gas, and coal, becoming the largest installed electricity capacity worldwide

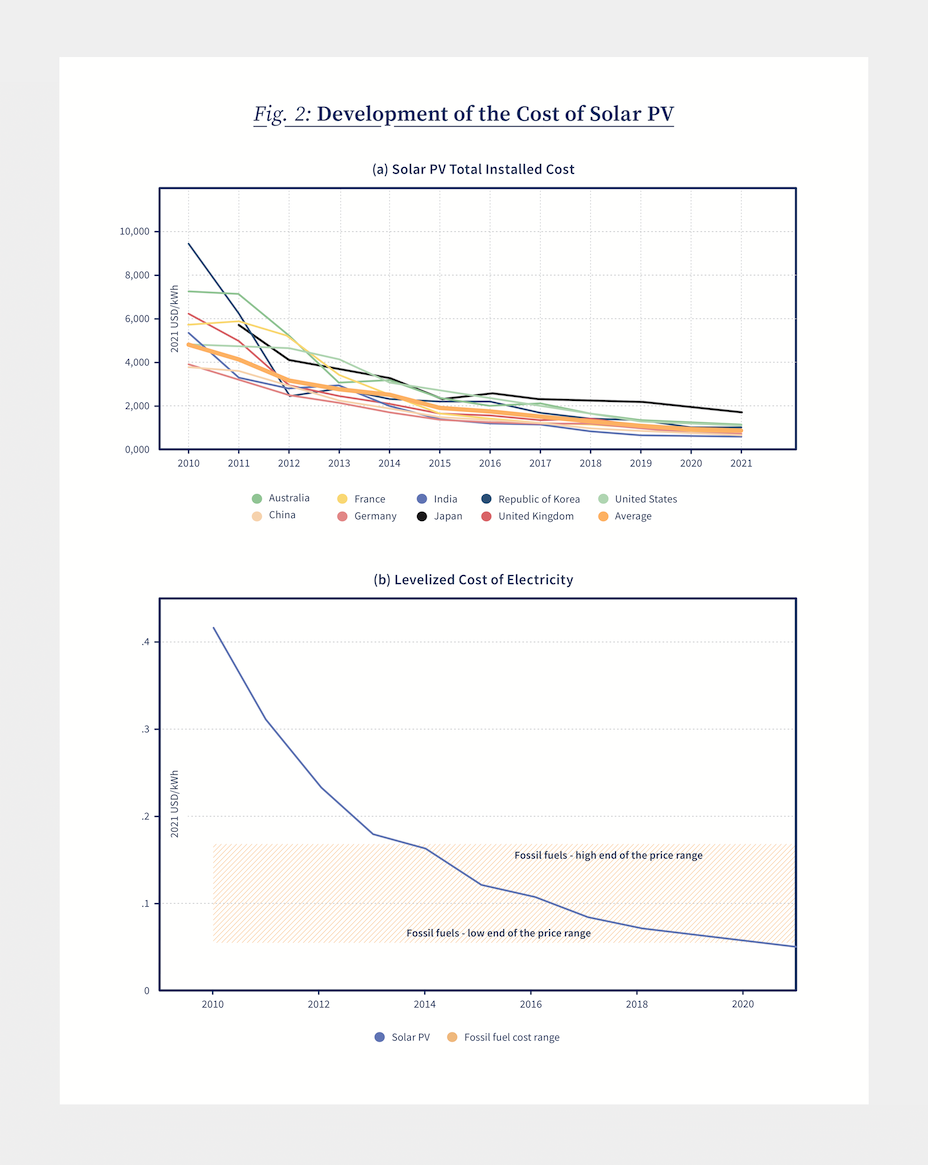

Underpinning this capacity expansion is a dramatic fall in the cost of solar PV. Figure 2a shows the total installed cost of solar PV in the years 2020 to 2021 for a set of countries, as well as the global average. The figure illustrates a sharp reduction in the cost of solar PV over time. In particular, the global average cost of solar declined by 88% between 2010 and 2021, a remarkable reduction that matches or even surpasses any other investment cost decrease, including the historical cost reduction of computers and peripheral equipment (Arkolakis and Walsh, 2023).

The decreasing cost of solar PV has positioned renewable energy technology as one of the cheapest forms of energy in many parts of the world. As shown in Figure 2b, the global weighted average levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) of new utility-scale solar PV is now below the lower end of the price range of fossil fuel-fired power generation options.5

The decreasing cost of solar PV has positioned renewable energy technology as one of the cheapest forms of energy in many parts of the world.

In this Kühne Impact Series, we demonstrate how the global diffusion of clean technology through international trade has played an important role in the dramatic cost reduction in solar globally. Specifically, we discuss China’s substantial expansion in solar PV production, making China the leading global producer since 2007, and its role in bringing down the cost of solar energy worldwide. Through comparisons to a predicted counterfactual cost development of solar PV in the absence of China’s expansion or absent open international markets, we show that international trade is essential in the global diffusion of clean energy technology as it ensures that all countries benefit from the lower cost of clean energy technologies. Thus, in addition to the green sourcing potential of international trade discussed in the previous Kühne Impact Series, we highlight that the global diffusion of clean technology is another important channel through which international trade matters in the fight against climate change.

We conclude by discussing potential challenges for the further global diffusion of clean technology. In particular, we discuss the vulnerability of the current geographical concentration in global supply chains, the US-China and EU-China “Solar Trade War,” and the slowdown in high-quality solar energy inventions.

... because International Trade Leveraged a Chinese Solar Boom

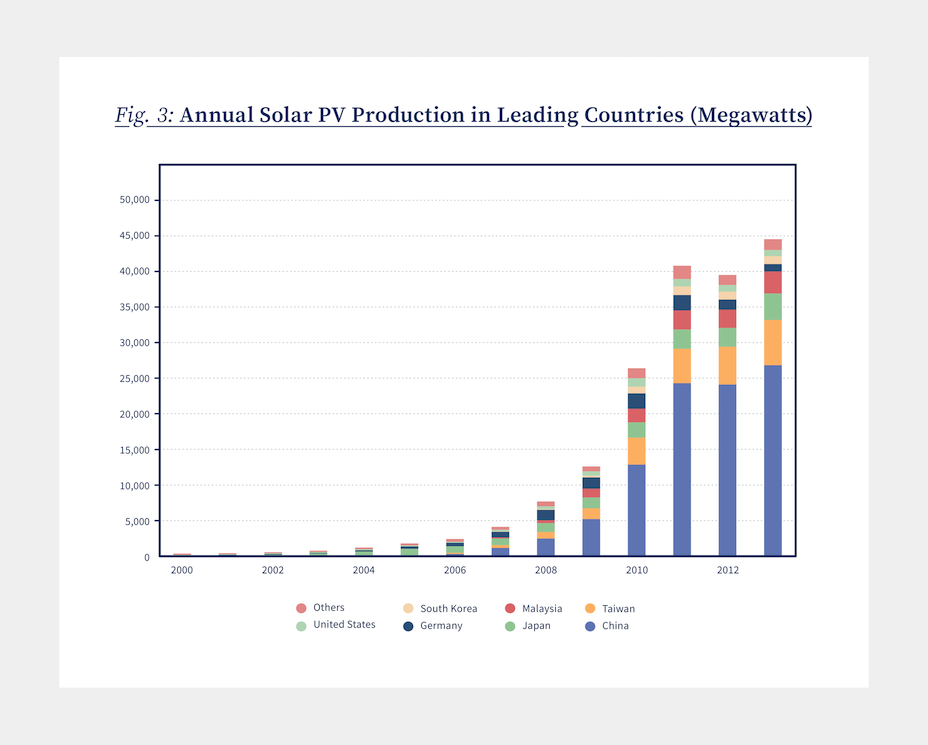

To illustrate the drivers behind the rise in solar PV and the role of international trade in clean technological diffusion, Figure 3 shows the annual production of solar PV in the leading producing countries. The figure shows that an expansion in China’s production largely drives the overall increase in production: the global solar boom is largely a Chinese solar boom. Starting from almost zero in 2000, China’s global share of solar PV production has risen sharply, making China the leading producer globally since 2007. Today, China’s share in solar PV production exceeds 80%, which is more than double its share of global demand, making China the leading exporter of solar PV globally.6

The expansion of the solar industry in China is a result of the cost-competitiveness of Chinese firms, which is itself due to several factors. First, Chinese firms benefited from low labor costs compared to previous incumbents. Second, the Chinese government enacted a range of industrial policies, including subsidies, to support a sector that it viewed as strategic (see, e.g., Banares-Sanchez et al., 2023). Third, a demand push allowed Chinese firms to benefit from economies of scale and learning by doing.

The global diffusion of clean technology is another important channel through which international trade matters in the fight against climate change.

This demand push originated from countries such as the US, Germany, and other member states of the European Union with commitments to reaching climate neutrality by 2050 (Nemet, 2019). That is, international trade is directly responsible for the Chinese solar boom.

China has been instrumental in bringing down the cost worldwide for solar PV, enabling faster clean technology adoption.

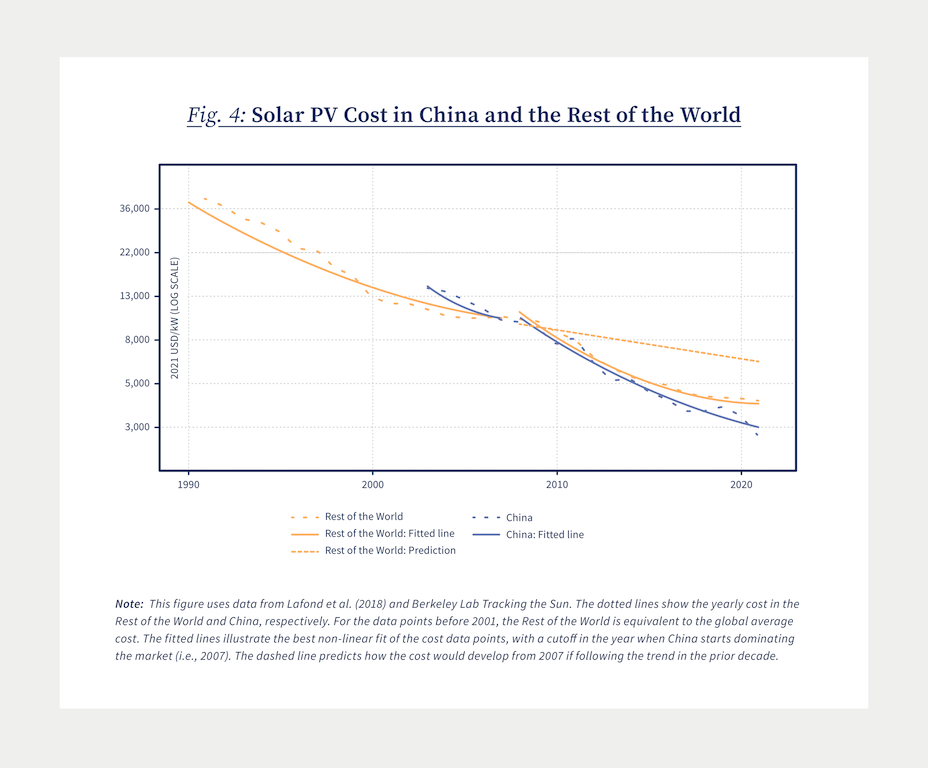

China has been instrumental in bringing down the cost worldwide for solar PV, enabling faster clean technology adoption. We illustrate this in Figure 4. The dotted lines in the Figure show the yearly development of the cost of solar PV produced in China and the Rest of the World, respectively, on a log scale.7 In addition, the figure illustrates fitted lines, i.e., the best non-linear fit of the solar PV cost data points. The fitted lines represent the general trends in the cost of solar in China and the Rest of the World. They are estimated separately for the years before and after 2007, to demonstrate the changed trajectory when China starts dominating the market. Finally, the dashed line prolongs the pre-2007 trend for the Rest of the World into the post-2007 time period.

Three facts emerge. First, the figure reproduces the sharp decline in the cost of solar PV since the year 1990. Second, it shows that from 2007 onward, the cost of Chinese solar panels has been lower than that in the Rest of the World and has declined faster (the blue line is below the yellow and steeper). Third, and perhaps most importantly, there is a clear trend-break in 2007, even for the Rest of the World: costs have declined substantially faster than on the pre-2007 trend (the yellow line is steeper than the dashed line).

How large was China’s role in reducing solar PV costs? And subsequently how costly would it be to shut down trade with China in solar PV? Figure 4 can provide some guiding answers. The first role of international trade is that it allows all countries to access the cheaper Chinese solar panels. The gap between the blue and the yellow line in 2021 represent 18% of the price decline since 2007. In turn, shutting down trade with China today would remove the opportunity for the Rest of the World to access solar PV at a 22% lower cost.

These numbers are, however, most surely lower bounds. International trade and globally integrated solar PV value chains allow producers in the Rest of the World to rely heavily on China both for sourcing inputs and for manufacturing (i.e., off-shoring of production). Indeed, trade patterns reveal that solar PV supply chains have become increasingly globalized over the past two decades. Trade in the HS subheading where selected solar PV components are classified increased significantly from around US$ 111 billion in 2005 to slightly more than US$ 300 billion in 2019. This role for international trade is reflected in the trend break in the solar PV costs for the Rest of the World post-2007.

We can then use the prediction for the Rest of the World (the dashed yellow line in the figure) as a rough counterfactual for the cost development of solar PV in the absence of any form of international trade in the solar sector with China. Specifically, compared to this counterfactual, trade with China has contributed to reducing the cost of solar PV by around 63% since 2007 and fully shutting down trade with China today could raise prices by up to 133% (corresponding to the gap between the blue and the dashed line). Since the demand factors discussed above may also have played a role in the cost development and since some of the cost reductions achieved in Chinese plants have now spilled over to the Rest of the World, these numbers are likely upper bounds.

Still, combining our upper- and lower-bound estimates, Figure 4 makes clear that keeping markets open to trade is important to ensure that all countries can benefit from lower cost of solar PV. Taken together, our findings highlight that the global diffusion of clean technology is an important channel through which international trade matters in the fight against climate change.

The Future of International Trade and Solar Panels

While pushing down the cost of solar energy technology adoption, China’s expansion in solar PV production and its dominance in the supply chain have led to several concerns, with possibly important consequences for the further global diffusion of clean energy.

One such concern is the considerable vulnerability associated with the level of geographic concentration of solar PV production. China’s share in all manufacturing stages exceeds 80%, and is predicted to continue increasing to reach 95% by 2025 (IEA, 2022). This level of concentration in any global supply chain represents a considerable vulnerability as it opens up for potential disruption from both domestic policy changes and geopolitical events. Recent disruptions, including the Covid-19 crisis and the war in Ukraine, have further raised attention to such risks, emphasizing the importance of diversifying solar PV supply chains to improve long-term resilience against exogenous shocks.

The cost competitiveness of existing solar PV manufacturing is a key challenge to diversifying supply chains. China is currently the most cost-competitive location to manufacture all components of the solar PV supply chain, making diversification difficult without dedicated industrial policies.

A second concern relates to the extent to which China’s cost competitiveness is due to numerous human right violations, pushing down the cost of labor. The vast majority of solar panels have significant exposure to the Xinjiaan region in China, where the government of China has imposed a region-wide, ethnically targeted program of state-imposed forced labor upon the Uyghur community and other minoritized citizens of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (UN OHCHR, 2022; Crawford and Murphy, 2023).

Ensuring that the transition to renewable energy is not contributing to human rights violations is essential and has been increasingly highlighted by the solar industry, governments, and consumers. Since 2021, there has been a significant change in solar industry sourcing toward other parts of China but also abroad. This change is partly a result of regulations and a ban on imports of products from this area. However, the increasing lack of transparency in solar supply chains makes it difficult for consumers, procurers, investors, and governments to identify a solar module not made with Uyghur forced labor. This threatens the public trust in the solar industry and, therefore, the further adoption of solar energy.

Partly as a result of these concerns, but mainly due to arguments that Chinese solar PV was unfairly subsidized and harmed the domestic industry in the EU and the US, tensions in solar trade between US-China and EU-China escalated into a “Solar Trade War” in 2011. Since then, the number of antidumping, countervailing, and import duties levied against parts of the solar PV supply chain has reached 16 duties and import taxes, with eight additional policies under consideration.

While the trade dispute with the EU is currently largely resolved, initiatives from the US to further restrict imports from China are ongoing, leaving supply chains vulnerable to further trade policy risks. The current tension and the potential further escalations of trade disputes represent considerable vulnerabilities for the global diffusion of clean technology, as international trade is critical to provide the diverse materials needed to make solar panels and deliver them to final markets at a competitive cost.

Innovation in Solar is Slowing Down

Sustained technological advancement in clean technologies is essential for the transition to clean energy. It is therefore important to study whether China’s solar boom also had implications for solar energy inventions. In theory, increased international competition from China could induce technical upgrading and increase productivity in the Rest of the World, positively affecting innovation rates (Bloom et al., 2016). On the other hand, increased competition diminishes profit margins, possibly reducing research and development activities and thus reducing innovation (Aghion et al., 2005; Autor et al., 2020).

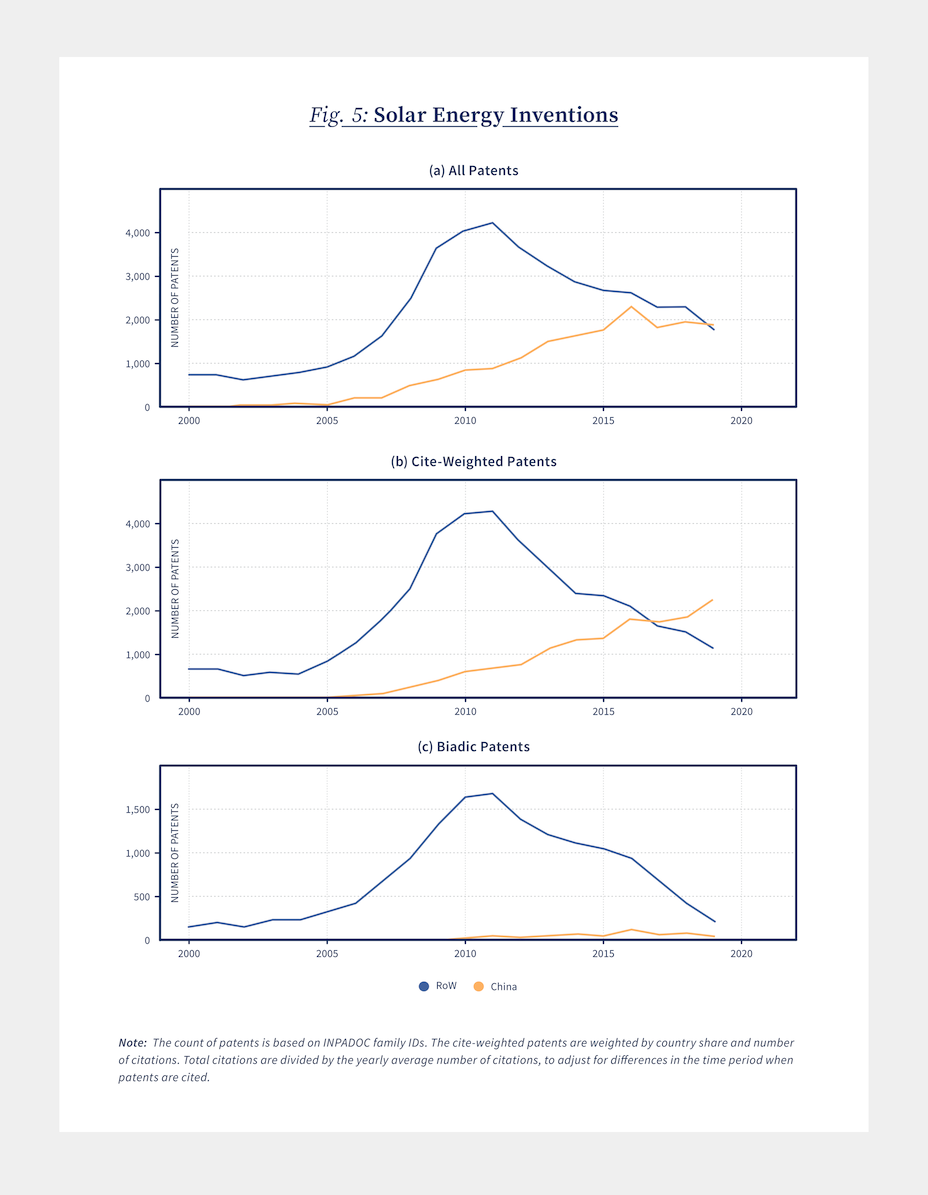

As shown in Figure 5a, the number of patents in China has substantially increased since 2005. However, the number of patents globally started to decline after 2010 as a result of a sharp decrease in the number of patents in the Rest of the World.

The global decline in solar energy inventions becomes even more pronounced when focusing on high-quality inventions. Figure 5b weighs the number of patents by the number of citations to account for the importance of a patent, showing a steeper decline in overall inventions. Moreover, Figure 5c restricts attention to patent families with patent applications in at least two countries (i.e., biadic patents), which is a definition commonly viewed as capturing innovations of sufficiently high quality. The number of biadic patents peaked globally in 2010, after which it dropped below the level reached at the beginning of China’s surge. Notably, China’s increase in biadic patents is very limited. Thus, although China is also increasingly dominating in solar energy innovation, overall solar inventions, particularly high-quality inventions, have been reduced.

While other factors (such as low gas prices and cuts in renewables subsidies in some EU countries) may also be at play behind the drop in innovations in the Rest of the World, these figures raise the concern that China’s dominance may hinder solar energy innovation. Benefiting from lower costs, Chinese producers displaced American, German and Japanese firms that produced more expensive solar panels but were also more innovative.8 While China’s role in the cost reduction of solar PV has enabled increased capacity and adoption, sustained innovation is important to ensure further diffusion of clean energy technology. According to the International Energy Agency’s roadmap to net zero emission by 2050, annual solar PV capacity additions need to more than quadruple to 630 gigawatts (GW) by 2030, and innovations play an important role in making this possible.9

The current tension and the potential further escalations of trade disputes represent considerable vulnerabilities for the global diffusion of clean technology.

Conclusion

The diffusion of cleaner energy technology is essential in the wider transition trajectories away from unsustainable production patterns. In this Kühne Impact Series, we discussed how the global diffusion of clean technology, such as solar panels, through international trade is an additional important channel through which international trade plays an important role in the fight against climate change.

Specifically, we demonstrated the role of China and international trade in the dramatic capacity expansion of solar PV. We made the case that China has contributed to reducing the cost of solar PV by up to 63% since 2007. Our predictions suggested that shutting down trade with China today could raise prices by as much as 133%, stressing the importance of keeping markets open to trade to ensure that all countries can benefit from a lower cost of solar PV. Moreover, we highlighted that threats to well-functioning global supply chains, including the vulnerability of the current geographical concentration in global supply chains and potential escalations of the “Solar Trade War,” as well as the slowdown in high-quality solar energy inventions, constitute potential challenges for the further global diffusion of clean technology.

- See, for instance, the World Bank’s Social Dimensions of Climate Change: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/social-dimensions-of-climate-change

- Energy production and use accounted for 76% of global GHG emissions in 2019 (Climate Watch, World Resource Institute (2020).

- IRENA, Renewable Capacity Statistics 2022. Note that since solar and wind are intermittent sources, the renewable electricity generation share is lower than its capacity share.

- A photovoltaic (PV) cell, commonly called a solar cell, is a non-mechanical device that converts sunlight (or artificial light) directly into electricity.

- The levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) measures the average net present cost of electricity generation for a generator over its lifetime. This number does not factor in the cost of batteries to address the intermittency of solar PV.

- The Chinese-manufactured share of global solar PV shipments reached 71% in 2022 (compared to 1% in 2004). Conversely, US solar PV shipments, while increasing in absolute numbers, declined as a percentage of global shipments from around 13% to 1.2% in 2022.

- Country-level solar PV cost data is not available prior to 2002 and we use global costs for the “Rest of the World” because China was not a significant producer then

- For instance, Carvalho et al. (2017) show that the biggest solar cell and module manufacturers all recorded losses in 2011 and 2012. Q-cells, a major German cell manufacturer, which was a leader in the market for most of the 2000s, went bankrupt in 2012.

- 9IEA (2021), Net Zero by 2050, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050, License: CC BY 4.0

- Aghion, P., N. Bloom, R. Blundell, R. Griffith, and P. Howitt (2005). Competition and Innovation. An Inverted-U Relationship. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120(2), 701–728.

- Arkolakis, C., and C. Walsh (2023). Clean Growth. NBER Working Paper 31615.

- Autor, D. H., D. Dorn, G. H. Hanson, G. Pisano, and P. Shu (2020). Foreign Competition and Domestic Innovation: Evidence from U.S. Patents. American Economic Review 110(7), 2044–2082

- Banares-Sanchez, I., R. Burgess, D. Laszlo, P. Simpson, J. Van Reenen, and Y. Wang (2023). Ray of Hope? China and the Rise of Solar Energy

- Bloom, N., M. Draca, and J. Van Reenen (2016). Trade Induced Technical Change? The Impact of Chinese Imports on Innovation, IT and Productivity. Review of Economic Studies 83(1), 87–117.

- Carvalho, M., A. Dechezleprêtre, and M. Glachant (2017). Understanding the Dynamics of Global Value Chains for Solar Photovoltaic Technologies. WIPO Economic Research Working Paper 40.

- Crawford, A., and T. L. Murphy (2023). Over-Exposed: Uyghur Region Exposure Assessment for Solar Industry Sourcing. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Hallam.

- IEA (2022). Solar PV Global Supply Chains. https://www.iea.org/reports/solar-pv-global-supply-chains

- Lafond, F., A. G. Bailey, J. D. Bakker, D. Rebois, R. Zadourian, P. McSharry, and J. D. Farmer (2018). How well do experience curves predict technological progress? A method for making distributional forecasts. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 128, 104–117.

- Nemet, G. F. (2019). How Solar Energy Became Cheap: A Model for Low-Carbon Innovation. London: Routledge.

- UN OHCHR (2022). OHCHR Assessment of Human Rights Concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China.

- We thank Carole Marullaz for providing data and illustrations on solar energy inventions.

About the Series

The Kühne Center aims to establish itself as a thought leader on issues surrounding economic globalization – by conducting relevant research and making its insights available to a broad audience. The Kühne Center Impact Series highlights research-based insights that help to evaluate the current world trading system and to identify what works and what needs to be improved to achieve a truly sustainable globalization.

More Issues

Variable Carbon Pricing and the Environmental Gains from Trade

Optimal Carbon Tax for Maritime Shipping?

The Sustainable Globalization Index

The Distributional Effects of Carbon Pricing:

The Green Comparative Advantage:

Global Trade

The EU Emissions Trading System

The Hidden Green Sourcing Potential in European Trade

The European Green Deal

Post-COVID19 resilience

Africa’s Trade Potential

Buy Green not Local

A New Hope for the WTO?

Crumbling Economy, Booming Trade

Pandemic and Trade

The Dynamics of Global Trade in Times of Corona

EU Trade Agreements

Past, present, and future developments