Outline

In this Kühne Impact Series, we continue our analysis of carbon pricing and its effect on global emissions, production, and trade in more realistic configurations of heterogeneous carbon pricing across countries. We identify three key findings. First, heterogeneous carbon pricing is always less efficient than uniform carbon pricing, as it invariably increases the global real income cost of the scheme. Second, the potential of green sourcing in international trade to combat climate change can be maximized through a targeted taxing scheme involving a select group of key players, provided they are both major producers and significant polluters. Finally, and perhaps contrary to intuition, heterogeneous carbon pricing is not a guarantee of increased fairness across countries. In fact, it is more often a source of increased inequalities.

The Kühne Center for Sustainable Trade and Logistics has long advocated for using international trade as a tool in the fight against climate change. We introduced the concept of Sustainable Globalization, defined as the global pattern of trade that would prevail if carbon were priced at its social cost.

In an earlier Kühne Impact Series, we simulated this concept of sustainable globalization under a uniform global carbon tax.1 The study revealed two key messages: first, that a global carbon tax is an extremely effective tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions; and second, that over a third of this reduction is achieved by leveraging countriesʼ green comparative advantage in international trade.

In a subsequent study, we addressed the political criticisms surrounding a global carbon tax, demonstrating that a uniform tax across countries can have adverse distributional effects, disproportionately penalizing poorer nations.2 Consequently, we explored the feasibility of international transfers under the UNFCCC principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibility (CBDR). We found that a combination of a uniform tax and a polluter-pays transfer scheme is equally effective at reducing emissions while facilitating a politically desirable redistribution of climate action costs.

A global carbon tax is an extremely effective tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

In this edition of the Kühne Impact Series, we extend our reflection by moving away from the concept of a global and uniform carbon tax to explore more realistic climate policies featuring heterogeneous carbon prices across countries. To stay aligned with existing public policies, we consider two taxation schemes: a unilateral carbon pricing scheme within a selected “club” of countries equipped with a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), as currently implemented in the EU, and the IMFʼs proposed “International Carbon Price Floor Among Large Emitters” (ICPF).3 We study the implementation of the ICPF in four different scenarios:

- Scenario 1:

ICPF implemented for a restricted club of countries (EU, China, U.S., India, Canada, Great Britain) - Scenario 2:

ICPF implemented for all G20 countries - Scenario 3:

ICPF implemented for a club of key countries (EU, China, U.S., India, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil) - Scenario 4:

ICPF implemented for all countries

Our primary focus is to assess whether international trade can continue to serve as a positive force in combating climate change under these frameworks, and whether these policies can achieve a more desirable level of fairness in climate action. We compare the performance of these taxation models to the scheme we identified as optimally balancing emissions reduction and fairness among nations: the uniform carbon tax approach, complemented by international financial transfers to harmonize the real income costs associated with emissions mitigation across different countries.

Three key findings emerge from our analysis. First, heterogeneous carbon pricing is consistently less efficient than uniform carbon pricing, leading to a higher global real income cost. Second, the green sourcing potential of international trade in fighting climate change can be exploited to its fullest with just a select group of key players as part of a taxing scheme provided that they are both major producers and significant polluters. In that respect, a climate club scheme with a CBAM is more efficient than the ICPF. Finally, and perhaps contrary to intuition, heterogeneous carbon pricing is not a guarantee of increased fairness across countries. In fact, it is more often a source of increased inequalities. A climate club of key players with CBAM is highly unfair, but the same club following the ICPF would be a little fairer.

Large environmental gains from trade can be achieved with just a small number of countries

The strength of a global and uniform carbon tax lies in its ability to adjust the relative prices of goods and services to accurately reflect their environmental impact. Beyond merely curbing consumption and production, especially of high-emission goods (via a scale and composition effect), it also encourages individuals to choose the greenest producers for any given product, thereby unlocking the green sourcing potential of international trade (sourcing effect).

This raises the question of how such incentives play out in a more realistic world where carbon is only taxed in a few countries. To study this, we simulate a world economy with incremental introduction of the carbon tax across countries, in the spirit of a growing “climate club.”4 Concretely, we start from a world with no carbon tax anywhere and compare it to a world with a carbon tax only in the EU. We then allow the carbon tax to be adopted in the EU and the U.S., in the EU, the U.S., and China, and so on. Figure 1 depicts the relative global emissions reduction achieved with each new member (relative to a world with no carbon tax), as well as the relative role of the scale effect (aggregate decrease in consumption and production), the composition effect (relatively stronger decrease of production and consumption of brown goods), and of the sourcing effect (green sourcing of any given good through international trade) in the achieved emission reduction. Note that in this scenario, the value of the carbon tax remains the same for all countries. It is just introduced progressively.

Figure 1 conveys two main messages. First, it highlights the significant discrepancy in the contributions of different countries to global emissions reduction. Countries with substantial production capacities and high pollution levels, such as the U.S., China, or Brazil, play a disproportionately large role in the potential emissions reduction achievable through a carbon tax. To put this into perspective, a global uniform carbon tax set at $100/t CO2-eq would result in a 27.6% reduction in global emissions. However, by implementing a carbon taxation scheme involving only the EU, the U.S., China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil, and South Africa, we already achieve an 18.5% reduction in global emissions, which amounts to two-thirds of the maximum achievable reduction.

Second, and more notably, our simulation reveals a relatively stable trend in the significance of the green sourcing effect. When the EU acts as the sole member of the “carbon tax club” (without CBAM), international trade contributes minimally to emissions reduction, accounting for just over 5%. The addition of the U.S. has little impact on this figure, but the inclusion of China substantially enhances the role of the sourcing effect, increasing it from 10% to 22%. As more countries join the club, including India, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil, and South Africa, the maximum potential contribution of the green sourcing effect to emissions reduction is realized, reaching approximately 38%.5 In essence, this highlights that the unlocking of the green sourcing potential of international trade requires the participation of only a few key players.

Countries with substantial production capacities and high pollution levels, such as the U.S., China, or Brazil, play a disproportionately large role in the potential emissions reduction achievable through a carbon tax.

With this in mind, we consider two different public policies that aim to achieve a similar idea of a limited but efficient “climate club” but with different approaches: a uniform carbon tax on a selected club of members paired with a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) similar to what the EU is currently implementing, and the IMF International Carbon Price Floor (ICPF). Both scenarios have in common that they appear to be politically easier to implement (more realistic) and potentially fairer, by allowing heterogeneous carbon pricing across countries.

In each scenario, we will focus on the following two questions: does the proposed scheme allow for a better exploitation of the green sourcing potential of international trade? Does the proposed scheme introduce more or less fairness between the Global North and the Global South?

To address these questions, we will examine several key indicators compared to a clearly defined benchmark: a hypothetical scenario producing the same emissions reduction as the one analyzed with a global and uniform carbon tax, coupled with “fair” transfers intended to equalize the real income cost across countries. Efficiency of the scheme will be assessed by comparing the global real income cost. Exploitation of the green sourcing potential of international trade will be evaluated based on the contribution of the sourcing effect to the global emissions reduction. Lastly, fairness will be measured by comparing the amount of North-South transfers needed to maintain equal real income costs for all countries.

A Climate Club of a few selected key players with a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is less efficient and less fair than a uniform carbon tax with transfers while only slightly improving the exploitation of the green sourcing potential of international trade

The European Union stands as a leading political entity in the global battle against climate change. It launched its carbon pricing initiative with the introduction of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS)6 in 2005, positioning itself as one of the first “carbon clubs” in the world. The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) has been proposed in 2021 to allow European companies to remain competitive in a world where the EU imposes a unilateral carbon price on its producers. In simple terms, one can consider the EU ETS as a carbon producer tax: any European producer must pay for a right to emit GHG emissions over the course of their production process. This makes the price of their output relatively more expensive, and therefore less attractive than foreign goods produced with no carbon tax. To restore the competitiveness of these producers within the EU, the CBAM imposes a similar carbon price on the consumption of goods imported into the EU if no carbon tax has been applied on them prior to entry.7 “By confirming that a price has been paid for the embedded carbon emissions generated in the production of certain goods imported into the EU, the CBAM will ensure the carbon price of imports is equivalent to the carbon price of domestic production […].”8

In simple terms, one can consider the EU ETS as a carbon producer tax.

We simulate this scheme in our model to exploreits impact on international trade dynamics. Specifically, our simulation posits a scenario where the EU unilaterally levies a carbon tax of $100/t CO2-eq on its producers and imposes a consumption tax on all imports. This effectively establishes a carbon price on all trade flows within the EU and between the EU and the rest of the world, while all other international exchanges remain unaffected.

We first compare this with a scenario in which the EU imposes a carbon tax on its producers, but without carbon border adjustment, which mirrors the traditional EU ETS. Quantitatively, it is first important to notice that the impact of a “EU-only climate club” on global emissions is not negligible but somewhat limited. We find that imposing a carbon tax on the EU only would reduce global emissions by 1.3%. Additionally imposing a CBAM on EU imports would lead to a total decrease of 1.4% of global emissions. This can be explained by the fact that production is already relatively clean in Europe compared to the rest of the world, and that trade within the EU is relatively strong.

What is more interesting to us is to understand how this impacts EU countries and their trading partners. Figure 2 depicts the real income change induced by the “EU-only” climate club on all countries, with and without CBAM. The figure carries three key messages. First, it is immediate to see that a “EU-only” climate club would “hurt” the European countries by making their product relatively less competitive. We see that the majority of the other countries would experience real income gains due to a trade diversion effect. Second, the introduction of a CBAM somewhat mitigates these initial effects: the real income effects on EU member countries are substantially lower (and sometimes become positive in the case of Spain or Austria for example), while the real income effects on all other countries remain quite stable. It therefore appears that the announced objective of restoring EU producersʼ competitiveness would be achieved with a CBAM. Third and more interestingly for us, the implementation of the CBAM would mostly hurt countries for which the EU is an important trading partner: the largest real income losses from going from a world with a “EU-only” climate club to a “EU-only” climate club with CBAM would be experienced by Morocco (–0.27 p.p.), Tunisia (–0.23 p.p.) and Great Britain (–0.08 p.p.).

This practical example suggests that credible policies such as the EU ETS coupled with a CBAM could bring some emissions reduction while focusing the carbon price on a limited number of countries. The question is whether this can be efficient, exploit green trade, and be fair when extended to additional countries.

To push this thought experiment a bit further, we simulate a world economy where additional countries join the climate club while imposing CBAM to the rest of the world. We perform the same exercise as for Figure 1, only now, members of the climate club also impose a carbon tax on imports from non-member countries. Note that countries excluded from the club neither impose a carbon tax on their production nor on their consumption. Figure 3 reflects this expanded scenario, akin to Figure 1, exploring the implications of establishing a climate club with CBAM as opposed to maintaining the status quo.

It is striking to note that both Figure 1 and Figure 3 are extremely similar, down to the magnitude of the scale, composition, and sourcing effect. In terms of emissions reduction, we find that a restricted climate club with CBAM is marginally more efficient than a restricted climate club without it. This should not come as a surprise as more exchanges are affected by carbon pricing in the second scenario.

The progressive introduction of key players in the climate club confirms that the largest gains not only in carbon emissions but also in exploitation of the sourcing effect can be achieved with just a few countries. In fact, the CBAM exacerbates the role of these few key players in achieving this sourcing effect compared to a climate club without CBAM. To illustrate this latter point we trace the difference between the contribution of the sourcing effect in a world with a simple carbon tax on the consumption of members of a climate club, and a world with CBAM for that same carbon club in Figure 4.

We find that a climate club with CBAM can maximize the green sourcing potential of trade, but provided that a critical mass of countries is part of it. When the club only contains the EU, the sourcing effect is 8 percentage points smaller with a CBAM than without it. This can be explained by the different incidence of the carbon tax in the two schemes. A simple EU carbon club as we simulated it in Figure 1 imposes a carbon price on consumption. In other words, the price distortion occurs on both EU-produced goods and on imports within the EU. In the case of a carbon tax with CBAM, the EU-internal carbon price is applied on production, and the CBAM on consumption. This means that the price distortion generated applies both within the EU on EU-produced goods and imports coming in, but also virtually outside of the EU on EU exports. The key difference is that relatively greener EU exports are made relatively more expensive everywhere in the world. This constrains the green sourcing effect for non-EU countries, thereby explaining the 8 percentage point gap observed (and the negative sourcing effect for a “EU-only” climate club in Figure 3). We see however, that this logic is reversed as soon as a critical mass of countries (namely the EU, the U.S., China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil, and South Africa) enters the climate club. In that scenario (Scenario 3), the fact that the production of some of the largest producers and polluters globally is virtually taxed for all (because the tax is imposed on production within the club and therefore also on exports) suffices to improve the green sourcing potential of international trade.

Focusing therefore on a scenario with a climate club formed by the EU, the U.S., China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil and South Africa (Scenario 3), we now turn to our main exercise and measure its efficiency, its success in exploiting green trade, and its fairness against our benchmark: a scenario with a uniform global carbon tax, assuming that carbon is priced at a level such that the obtained global emissions reduction is identical (–19%), and international transfers such that the real income cost of the emissions reduction is equalized across countries. This corresponds to a “sustainable globalization” in a world with a carbon price of $60/t CO2-eq.

In such a scenario, the global real income cost of climate action would be 10.6% larger than in our benchmark scenario. In other words, such a climate club is relatively less efficient than a uniform global carbon tax. We have seen, however, that it would generate a larger sourcing effect (about 1 p.p. larger according to Figure 4), meaning that the potential of international trade to reduce emissions would be exploited more in this case.

Would this scheme achieve fairness? Comparing North-South transfers needed to equalize the real income cost of carbon pricing for all countries with our “key players” climate club (Scenario 3)9 to our uniform global carbon tax with “fair” transfers benchmark, we find that the “key players climate club” is less fair: it requires transfers of the order of $201 billions, that is 36% more than in our benchmark scenario. This can be explained again by the incidence of the carbon tax. As previously mentioned, the climate club implementing a CBAM imposes a tax on the production of member countries, consequently raising the prices of their goods globally. Simultaneously, the CBAM levies a tax on the consumption of imports, making goods from non-member countries more costly for club members. Considering a climate club that includes the world’s largest producers and consumers, the policy disproportionately impacts smaller, relatively browner countries that are not in the club. These countries face a dual penalty: their imports of greener goods become pricier, while their own exports become less attractive for the worldʼs largest consumers. Were the tax uniform across countries and applied within each country on consumption (as is done in our benchmark), the relative price increase of the largest producersʼ goods would translate into tax revenue for these smaller countries, instead of a pure penalty on their consumption.

A climate club of selected members imposing a carbon tax internally and coupled with carbon border adjustment is a more realistic and somewhat politically more acceptable way to reduce emissions.

To summarize, a climate club of selected members imposing a carbon tax internally and coupled with carbon border adjustment is a more realistic and somewhat politically more acceptable way to reduce emissions. In this world international trade contributes a little more to the overall emissions reduction achieved than in a world with a uniform carbon tax. The magnitude of this effect is, however, limited. It is otherwise less efficient and more importantly less fair than a uniform global carbon tax with North-South transfers. The argument according to which a heterogeneous carbon pricing would be fairer therefore does not hold here.

The concept of a climate club may be politically attractive to the extent that it only requires the coordination of a few key players. But the ideal group of key players that we have identified (EU, U.S., China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil and South Africa) is not homogeneous, both in terms of economic performance, geopolitical affinity, and in terms of historical responsibility towards climate change. This may partially explain why our climate club scenario is in fact less fair than a uniform carbon tax. The IMF proposed an alternative scheme designed to bring about more fairness through heterogeneous carbon pricing within the climate club: we now turn to the analysis of the ICPF.

The fairness benefits of the IMF International Carbon Price Floor scheme are outweighed by a significant decrease in efficiency

The International Carbon Price Floor (ICPF) is a proposal made by the IMF in June 2021 with the key ambition to match near-term climate goals with credible policy actions. To paraphrase the proposal, the scheme would rely on two key ingredients: (i) a small number of key large emitting countries would be the core “club” negotiating it, and (ii) the negotiation would focus on the minimum carbon price that each must put on their CO2 emissions. The argument in favor of a core “club” of members is to simplify negotiations by limiting the size of the initial setup.

Candidates retained in the proposal are either a group composed of Canada, China, the EU, Great Britain, India, and the U.S. (Scenario 1), or the whole of the G20 (Scenario 2). Focusing the negotiations on the price floors is in essence proposing a compromise between a global uniform carbon tax as advertised by most of the economists, and a climate club scenario similar to what we studied above. In their calibration, the IMF proposes three price floors: $75/t CO2-eq for advanced countries, $50/t CO2-eq for high income emerging economies (EME), and $25/t CO2-eq for low income EMEs.10

Taking this idea to its full potential, we calculate total emissions reduction, scale, composition, and sourcing effect, as well as welfare costs-equalizing transfers for several applications of the ICPF, and compare it against the relevant uniform tax with a fair transfer benchmark.

Focusing the negotiations on the price floors is in essence proposing a compromise between a global uniform carbon tax and a climate club scenario.

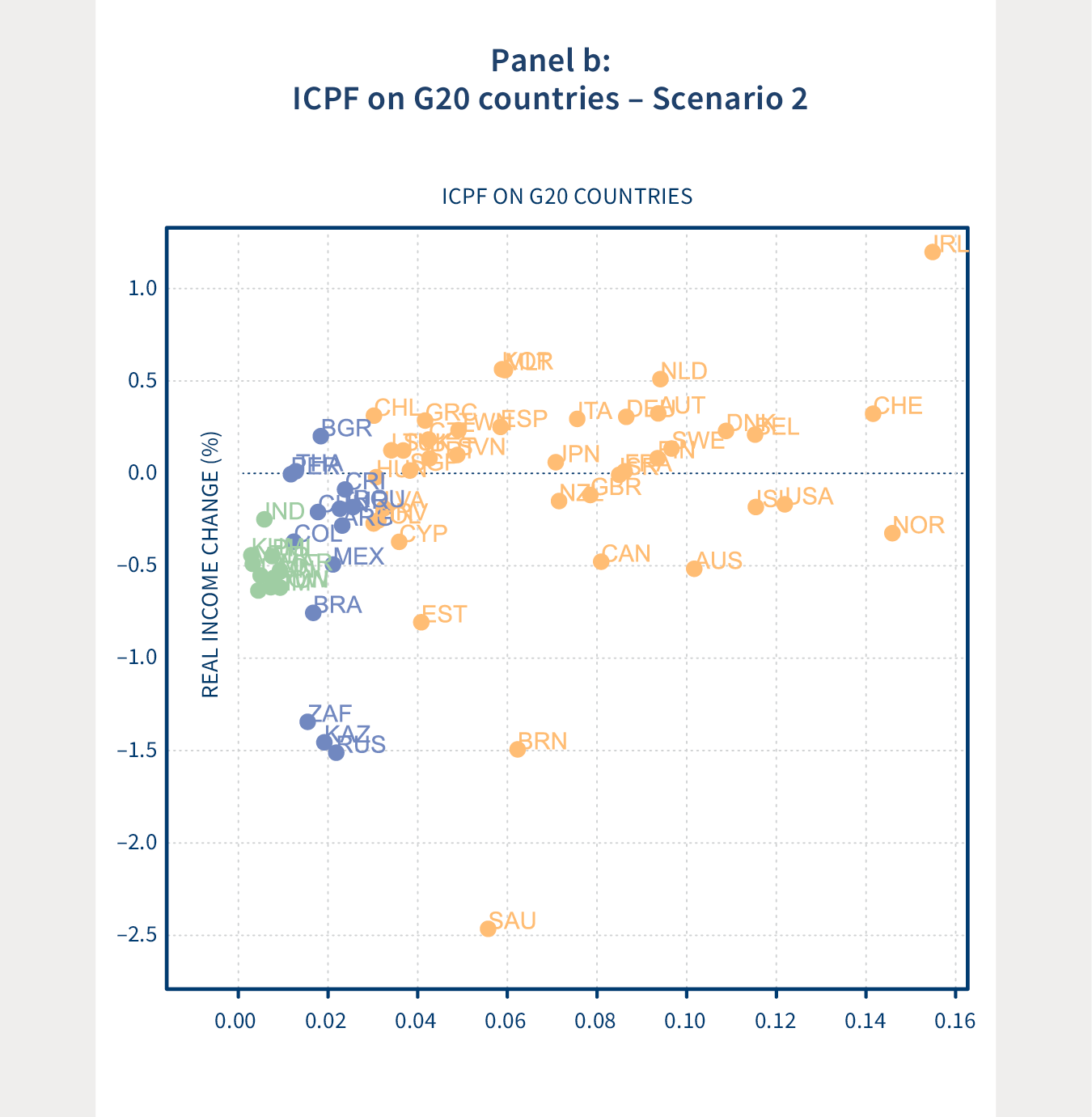

Our first point of focus is the exploitation of the green sourcing potential of international trade. Starting from the core idea of the IMF, we apply the ICPF scheme to the most restricted group, proposed by the IMF, of Canada, China, the EU, Great Britain, India, and the U.S. (Scenario 1). We find that such an application of the ICPF would reduce global emissions by 9.2%, and that the sourcing effect would contribute for 25% of this reduction, that is, less than the maximum contribution of one third that we have observed with a global and uniform carbon tax, or with a climate club. Second, we follow the other proposal of the IMF and include all G20 member countries in the ICPF (Scenario 2). Note that the carbon tax paid by G20 members will differ according to their economic development. In this scenario emissions are unsurprisingly reduced by more (13%), and the contribution of the sourcing effect reaches 33%. It thus appears that the sheer mass of member countries would play a key role in optimizing the role of international trade against climate change.

To understand whether these differences are only brought by the amount of club members, we explore a third scenario, namely the application of the ICPF to the club of countries that we identified as key players in the context of a uniform carbon tax coupled with a CBAM, namely the EU, the U.S., China, India, Indonesia, Russia Brazil and South Africa (Scenario 3). In this scenario, global emissions are reduced by 11%. Note that this is not much lower than in the G20 club case, revealing once again the importance of a few key countries in global emissions. What is more interesting to us is the contribution of the sourcing effect in this scenario: we find that 35% of the emissions reduction can be explained by green sourcing; this is more than in the G20 scenario. This reveals that unlocking the green sourcing potential of international trade is not only a matter of mass. Rather, the green sourcing becomes relevant when the key producers and consumers of our world are internalizing the environmental cost of their exchanges.

The climate club scheme, on the other hand, ensures that production of member countries is relatively more expensive everywhere, while maintaining a tax on imports.

Comparing briefly a “key players” climate club (with CBAM) to the ICPF scheme applied to the same group of countries, it is interesting to see that the green sourcing component is slightly lower in the ICPF case. This comes from the fact that the ICPF is a consumption tax, while the climate club imposes both a production tax on some countries and a consumption tax in some others. In the ICPF, each scheme member pays a tax both on goods they produce and consume within the club and on goods they import from external countries. However, their exports to non-member countries are not taxed, alleviating the competitiveness issue posed by the climate club but aggravating the absence of carbon pricing outside of the scheme. The climate club scheme, on the other hand, ensures that production of member countries is relatively more expensive everywhere, while maintaining a tax on imports.

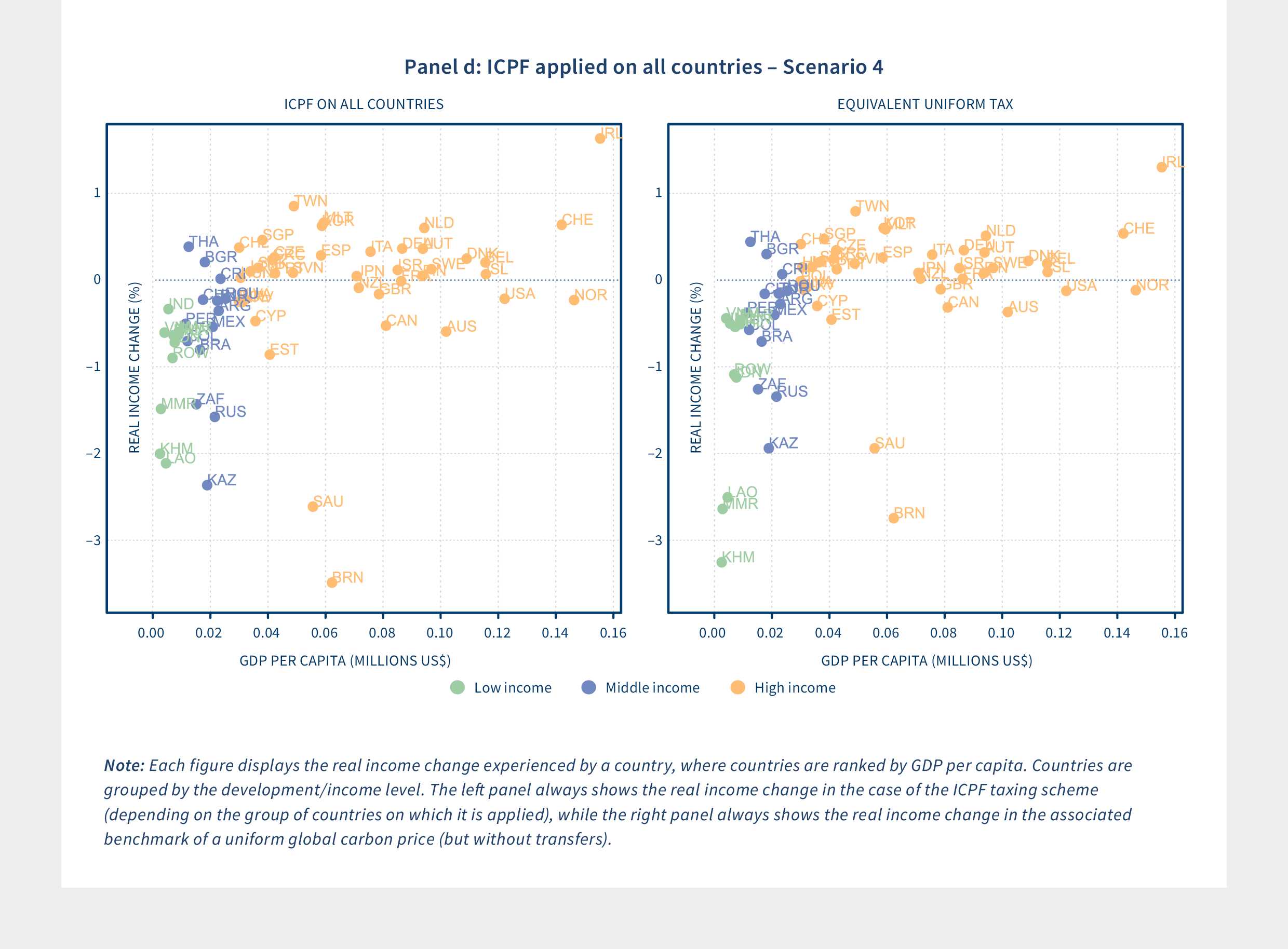

Finally, we analyze a scenario where all countries are participating in the ICPF scheme (Scenario 4), according to their level of economic development. Global emissions are reduced by 15.7%, which is equivalent to a global and uniform carbon tax of $47/t CO2-eq, and the green sourcing would contribute for 34.1% of the total, which remains lower than what can be achieved with a climate club on only a few key players.

The objective of the IMF with this proposed scheme however was not so much to achieve sustainable globalization but to reduce emissions with a “fairer” scheme than a uniform global carbon tax. We therefore now compare the welfare cost of the IPCF scheme with that of our benchmark, as well as the monetary transfers required between the economic North and the economic South to equalize per capita real income changes across countries.

We find that the initial ICPF scenario of the IMF including only Canada, China, the EU, Great Britain, India, and the U.S. (Scenario 1) is in fact the least fair of all, to the extent that the amount of North-South transfers needed would be 4.6% higher than with a global uniform carbon tax. In comparison transfers needed with a ICPF including G20 countries would require transfers 1.2% higher than in its uniform tax benchmark, and thus remain less fair. The ICPF applied to all countries would be the fairest to the extent that it would require 5.5% less transfers than a uniform carbon tax with fair transfers. Our proposal of an ICPF scheme applied to our identified key players (EU, U.S., China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil and South Africa) would be relatively fairer than its equivalent uniform tax benchmark, with required North-South transfers 3.5% lower. This is also to be compared to the climate club comprised of these same members that does not achieve fairness but on the contrary exacerbates inequalities across countries.

To understand these results, we can rely on the definition of the transfers we are considering: “fair” transfers are paid or received to equalize the real income cost of the taxing scheme across countries. Figure 5 illustrates how real income changes in each ICPF version (without transfers) and compares it to its uniform tax benchmark (also without transfers). One must then imagine transfers as the tool for bringing all countries back to a single common real income cost value.

Two key insights emerge from these plots and can explain our results. First, it is evident that the ICPF scheme, when applied to a select group of countries – whether it be the IMF restricted club (panel a), the G20 (panel b), or our curated group of key players (panel c) – successfully reduces the real income cost borne by low income countries. This is illustrated by the proximity of these countries to the zero real income cost line. Not only does the scheme decrease the value of the real income costs, but it also lessens the dispersion among low income nations.

Applying the ICPF to our select group of key players proves fairer, imposing

meaningful real income costs on high income countries more uniformly than a standard carbon tax.

Second, while the scheme mitigates some real income costs, it does not alone guarantee “fairness” in terms of our monetary transfers. Middle-income countries tend to be adversely affected by these schemes, necessitating financial compensations. Particularly, China becomes a net recipient of these transfers across various configurations, which represent a significant amount of transfers given its large population. Conversely, the real income cost for high income countries remains relatively stable, showing little deviation from the baseline.

The ICPF scheme, when applied to our select group of key players, proves fairer than its associated benchmark as it imposes meaningful real income costs on high income countries, albeit more uniformly than a standard carbon tax would (notably, countries like Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, significant polluters due to their primary economic activities, experience a mitigated tax impact and align more closely with other high income nations). Ultimately, applying the ICPF across all countries emerges as the fairest approach by reducing disparities in real income costs through a heterogeneous carbon cost tailored to each countryʼs development level, thereby fostering greater equity among nations.

In terms of efficiency, the IPCF scheme proposed by the IMF for a restricted group of countries (Canada, China, the EU, Great Britain, India, and the U.S.) not only ranks as the least fair but also exhibits the lowest efficiency among these schemes, with a measured welfare cost 1.3 times larger than that of a uniform carbon tax (132%). None of the examined scenarios surpass the efficiency of the uniform “fair” tax benchmark. However, it is evident that the inclusion of more countries in the scheme reduces inefficiency. The most efficient option is thus the ICPF applied globally, resulting in additional welfare costs limited to a 12% increase.

Figure 6 summarizes all these findings across ICPF scenarios. We highlight three key messages. First, while there is an efficiency cost attached to all schemes, fairer does not necessarily mean less efficient. Second, mass is not enough to unlock the green sourcing potential of international trade. Allowing countries to exploit their green comparative advantage is only possible when (i) a sufficient number of countries participate in the scheme and crucially (ii) the worldʼs key traders are part of it. Third and finally, it is unclear whether the IMF proposal would be significantly fairer than a simple global uniform carbon tax paired with North-South transfers (as already committed by some countries). Indeed, the IMF ICPF scheme applied to all countries of the world would be 12% more costly in terms of real income change, while reducing the required transfers by a mere 6%.

Conclusion

In this Kühne Impact Series, we continued our analysis of carbon pricing and its effect on global emissions, production and trade, in more realistic configurations of heterogeneous carbon pricing across countries: namely a climate club with a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and the IMF-proposed International Carbon Price Floor (ICPF).

We identify three key findings. First, heterogeneous carbon pricing is always less efficient than uniform carbon pricing, insofar as it always increases the global real income cost of the scheme. Second, the green sourcing potential of international trade in fighting climate change can be exploited to its fullest with just a select group of key players as part of a taxing scheme provided that they are both major producers and significant polluters. Finally, and perhaps contrary to intuition, heterogeneous carbon pricing is not a guarantee of increased fairness across countries. In fact, it is more often a source of increased inequalities.

We therefore remain an advocate of a global and uniform carbon tax shared by all countries, paired with pledged North-South aid transfers as the best policy tool to fight climate change.

Environmental comparative advantage along the path to net zero

So far, we have analyzed the environmental gains from trade based on emission intensities from 2018. In our forthcoming paper (Le Moigne et al. 2024), we also explore the evolution of the environmental gains from trade along the path to net zero, based on a Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Our main finding is that trade remains a strong force multiplier for climate action along the entire pathway.

Specifically, we focus on the relatively stringent RCP 2.6, aiming to limit warming to 1.5–2°C. We create a single, simplified emissions pathway that delivers RCP 2.6 by averaging across several Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) and climate models. We then replicate this simplified emissions pathway in our model by reducing the emissions intensities – either proportionately across countries (“Greener World”) or proportionately across countries of the Global North (“Greener Global North”).

Figure 7 shows that trade remains a strong force multiplier for climate action along the entire emissions pathway in both scenarios. To construct the figure, we simulate the impact of a $100/t CO2-eq worldwide carbon tax on greenhouse gas emissions along the emissions pathway. We then decompose the effect into the usual scale, composition, and green sourcing effects, and plot the green sourcing effect as a share of the total effect. Recall that the green sourcing effect captures the environmental gains from trade.

The intuition is that the environmental gains from trade are driven by environmental comparative advantage. Thus, as long as there are differences in relative emissions intensities across countries, there will be environmental gains from trade. However, the total greenhouse gas emissions reductions brought about by the carbon tax diminish along the pathway as there is progressively less to decarbonize. What remains roughly constant is the share of emissions reductions due the environmental gains from trade.

This intuition also explains why the green sourcing contribution is slightly higher in the Greener Global North scenario, as rising technological differences across countries magnify environmental comparative advantages.

- The Green Comparative Advantage: Fighting Climate Change through Trade. Le Moigne. Kühne Impact Series (01/2023)

- The Distributional Effects of Carbon Pricing: A Global View of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities. Le Moigne and Lepot. Kühne Impact Series (02/2023)

- Proposal for an International Carbon Price Floor Among Large Emitters. 2021. Ian W. H. Parry; Simon Black; James Roaf. IMF Staff climate note: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/staff-climate-notes/Issues/2021/06/15/Proposal-for-an-International-Carbon-Price-Floor-Among-Large-Emitters-460468

- The concept of “climate club” was first introduced by William Nordhaus, winner of the 2018 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. In his conceptualization, the climate club introduces carbon pricing among the clubʼs member states and levies a fee on all imports of goods from countries that are outside the club. We study both parts of this concept in turn.

- In Figure 1 the maximum of 40.5% is achieved by introducing the aggregate Rest of the World (ROW). Because it is an aggregate of several countries, we do not take this as benchmark.

- For a detailed explanation of the EU ETS, see our Kühne Impact Series on the topic: The EU Emissions Trading System: Becoming Efficient. Blanga-Gubbay, Khoban. Kühne Impact Series (02/2022)

- De facto, this aligns exactly with Nordhausʼ concept of a “climate club.”

- European Commission: Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism presentation page: https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en#:~:text=The%20EU’s%20Carbon%20Border%20Adjustment,roduction%20in%20non%2DEU%20countries

- Recall that in the absence of any carbon taxation, and despite pledges at the COP21, a grand total of $83.3 billions has been mobilized for climate financed in 2020. Aggregate Trends of Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013–2020. 2022. OECD

- We follow the World Bank allocation of countries to different levels of economic development in our simulations: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html

About the Series

The Kühne Center aims to establish itself as a thought leader on issues surrounding economic globalization – by conducting relevant research and making its insights available to a broad audience. The Kühne Center Impact Series highlights research-based insights that help to evaluate the current world trading system and to identify what works and what needs to be improved to achieve a truly sustainable globalization.

Author

Simon Lepot

Senior Research Fellow at the Kühne Center for Sustainable Trade and Logistics at the University of Zurich

More Issues

The Distributional Effects of Carbon Pricing:

Optimal Carbon Tax for Maritime Shipping?

The Global Diffusion of Clean Technology

The Sustainable Globalization Index

The Green Comparative Advantage:

Global Trade

The EU Emissions Trading System

The Hidden Green Sourcing Potential in European Trade

The European Green Deal

Post-COVID19 resilience

Africa’s Trade Potential

Buy Green not Local

A New Hope for the WTO?

Crumbling Economy, Booming Trade

Pandemic and Trade

The Dynamics of Global Trade in Times of Corona

EU Trade Agreements

Past, present, and future developments